Race and ethnicity, as measured by the Census

By Luc Schuster

April 26, 2019

This is an online version of our Boston Research Snapshot email newsletter from April, 2019. Sign up to get the newsletter in your inbox every month.

On May 8, 2019 we released Changing Faces of Greater Boston, a joint project produced by researchers from Boston Indicators, UMass Boston and the UMass Donahue Institute. The report tells the fascinating story of our region’s evolving racial and ethnic diversity. After a decline during the mid-20th century, we’re now several decades into a new global wave of immigration, bringing Boston back to its roots as a city of immigrants. Between 1990 and 2017, every one of Greater Boston’s 147 cities and towns saw an increase in the non-white share of its population.

Our ability to track these important changes is dependent upon data gathered by the U.S. Census Bureau and made available to local researchers like us, among many other users. This data provides rich detail unavailable from most other sources, but it’s not without its flaws. For example, the Census Bureau’s current approach actually involves two separate questions about a respondent’s racial/ethnic background: 1) What is the person’s race? and 2) Is the person of Hispanic, Latino or Spanish origin (or “ethnicity”)?

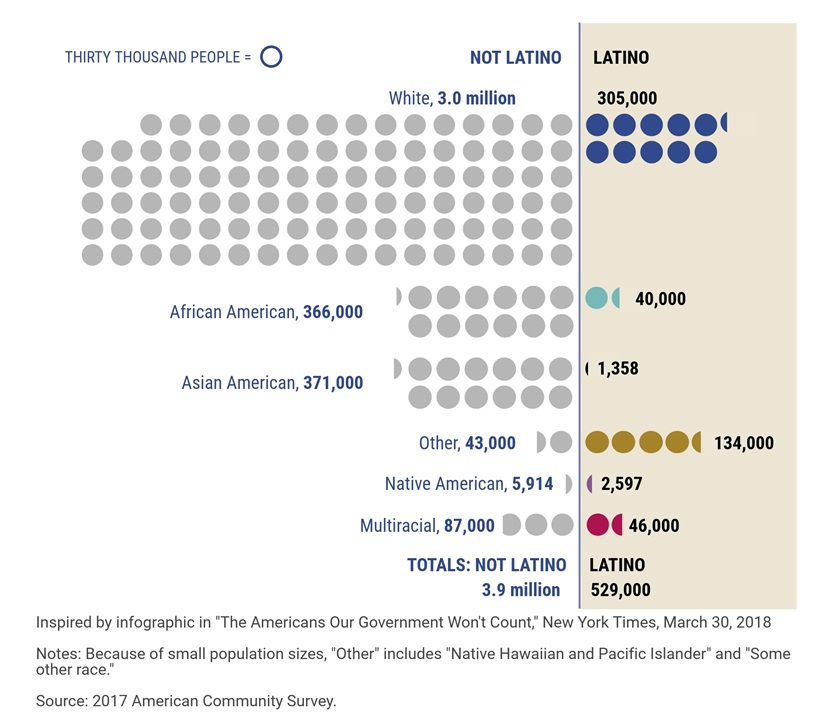

The graphic below shows how these two questions lead to overlapping counts. The horizontal clusters represent people’s race, and the two vertical clusters represent people’s ethnicity (Not Latino or Latino). There are roughly 3.3 million white people in Greater Boston, for instance, and over 300,000 of them also identify as Latino.

On the Census, people are asked to report race separately from ethnicity.

Greater Boston's population by race and ethnicity. 2017.

At a minimum, these separate questions can lead to confusion. But it also means that people who primarily identify as Latino are also expected to select a race. Note that the vast majority of people who select “Other” as their race also identify as of Latino ethnicity—of roughly 177,000 people in Greater Boston who select “Other,” 134,000 also select Latino. This suggests strongly that many Latinos do not additionally identify with one of the Census-defined race categories, so they select “Other” as a fallback.

The above graphic does reflect an important improvement made to the Census race/ethnicity questions in 2000, when respondents were finally allowed to select as many race categories as reflected their true identity, rather than being forced to select only one. In Boston, our multiracial population made up 4.4 percent of the city in 2000 and then grew to 4.9 percent by 2016. These multiracial estimates still almost certainly understate the true share of individuals with multiple racial/ethnic backgrounds. While respondents now have the option of selecting two or more races, they still do not have the option of selecting multiple ethnicities. Even though growing numbers of people have one Hispanic/Latino parent and one non-Hispanic/Latino parent, people are only given the binary option of selecting one or the other.

Despite these issues, the Census is still our best tool for understanding who we are as a city, state and country. The next decennial census, which is used for apportioning political representation and distributing billions of dollars in federal funding, begins one year from now on April 1, 2020. For more detail on why getting a fair and accurate count is so important for our state, please see Census 2020, Explained: How It Works and What’s at Stake for Massachusetts.

Additional resources on how the Census measures race and ethnicity:

- An interactive infographic from the Census Bureau detailing all changes to race and ethnicity questions from 1790 to 2010.

- Increasing numbers of people are selecting “Some Other Race.” The Rise of the American ‘Others’ explores the trend.

- In advance of the 2020 Census, the Census Bureau considered merging the separate race and ethnicity questions into one, although ultimately the change wasn’t adopted. An article from FiveThirtyEight details how it might have led to more accurate counts of Arab Americans, in particular.

- The Census Bureau has predicted that the United States will become “majority-minority” by 2045. But these estimates depend on counting all children of mixed families as non-white. An article in the American Prospect explains several reasons why “Census Bureau statistics have misled thinking about the American future.”