How Local Zoning Helped Create Our Region's Housing Crisis

By Luc Schuster

July 25, 2019

This is an online version of our Boston Research Snapshot email newsletter from March, 2019. Sign up to get the newsletter in your inbox every month.

As with any regulations, local zoning rules help us balance competing interests. Someone who owns a plot of land, for instance, is given significant leeway to do what they want with the property. But building a manufacturing plant in the heart of a residential neighborhood might be terrible for the neighbors. Local zoning is designed to balance these sorts of issues, allowing only certain types of development in certain areas. (How Land-Use Policies Shapes Our Lives from the Urban Institute provides great additional detail.)

The problem is that in areas like Greater Boston, local zoning regulations have often been used in ways that reinforce and even create patterns of residential segregation, a situation exacerbated by the small physical size of our cities and towns. A 10-square mile area might fall into a half-dozen communities, each with its own restrictions and requirements. While much of the policy discussion around segregation looks back at the lasting impact of racially biased policies like redlining, a focus on these historic injustices risks letting us off the hook for actions taken today. Current practices, many of which function through local zoning codes, also serve to perpetuate residential segregation and inflate housing prices.

Released just last week, The Greater Boston Housing Report Card 2019: Supply, Demand and the Challenge of Local Control, helps explain how these dynamics work. Municipalities with zoning codes that make it difficult to build multifamily housing tend instead to produce only single-family homes accessible only to a small segment of the population–this is referred to as “exclusionary zoning.” Our mental model for “segregation” often leads us to picture urban neighborhoods of color, but some of our region’s most intense segregation is also in our affluent white suburbs. These communities have produced very little multi-family housing and instead are composed mostly of expensive single-family homes affordable only to higher-income families, most of whom tend to be white. In addition to analyzing problems with our current approach to local zoning, the Housing Report Card also analyzes which cities and towns aren’t producing their fair share of housing for lower-income residents. It’s really worth the read.

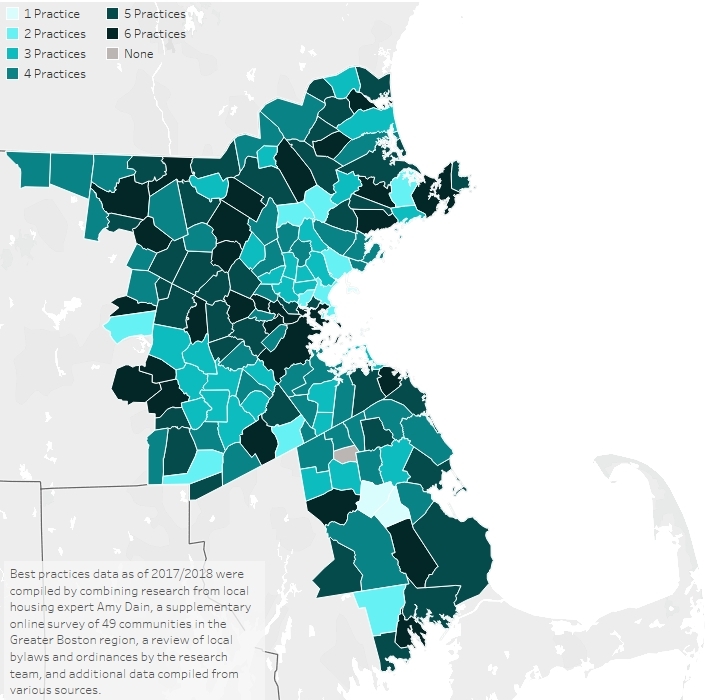

Boston Indicators helped edit the report and also created a two-part interactive online tool; 1) it maps which municipalities have adopted six key housing production best practices; and 2) it presents a range of local housing market data for each of the 147 cities and towns in the Greater Boston region.

Number of Housing Best Practices by Municipality

Fortunately, policymakers are increasingly recognizing the role that local decision making has played in creating our current housing crisis. The Report Card shows, for instance, that a growing number of Greater Boston cities and towns have revised their zoning codes to allow for multi-family developments in at least some neighborhoods. This represents good progress.

Not only can it be very hard to build new housing under current rules, oftentimes what’s actually allowed is even narrower than it initially appears. A recent New York Times interactive feature on the surprising share of major U.S. cities that is zoned only for single family homes got some recent attention and led an enterprising Cambridge resident, Christopher Schmidt, to do a similar analysis of Cambridge. As he describes in this useful twitter thread, only a small portion of the city is explicitly restricted to single family development. But after analyzing the zoning code more closely, he found that due to additional restrictions on housing—specifically, the lot size required per unit of housing—a total of 47 percent of the city is effectively limited to single-family development.

Relatedly, in many places zoning codes have been written so narrowly that the vast majority of the current housing stock would never have been permitted had it been proposed after the zoning rules had been written. An article in City Observatory quotes a Somerville planning office report as finding that “in a city of nearly 80,000 people, there are exactly 22 residential buildings that meet the city’s zoning code. Every single other home is too dense to be legal.”

It’s a little unfair to use Cambridge and Somerville as examples of zoning gone bad because, as this year’s Housing Report Card shows, they’re actually two of only a small number of inner ring suburbs that are building their fair share of housing to meet our regional needs. Further, both communities are actively considering important policy reforms that could help further. Cambridge is debating a unique affordable housing overlay proposal that would allow affordable housing developers to operate with fewer zoning restrictions when building projects that have all units set aside for lower-income residents. Somerville is also far along in a process of overhauling its zoning code to simplify the ordinance and allow for more residential development, especially around transit.

Even if these reforms lead to meaningful change, this city-by-city approach to addressing our shared housing challenges is almost certainly too piecemeal. It’s not that zoning is inherently problematic, but just that our hyper-local approach to these land use regulations has gotten out of control. Housing is a vital public policy issue of interest to everyone in the Commonwealth. The state shouldn’t be ceding so much of this important regulatory control to individual cities and towns. When it does, places too often tend towards restrictive rules that serve to exclude, rather than establishing rules that promote the broader good.