Why Our Current Criminal Justice System is not the Answer to the Opioid Crisis

By Anise Vance

November 30, 2017

A well-functioning criminal justice system should protect our neighborhoods from immediate threats, justly punish wrongdoers in a way that avoids cruelty and provide robust supports for offenders to get back on the right track. As demonstrated by the data in this brief, our state’s increasing criminalization of people with substance abuse problems has likely violated all three of these principles. Recidivism rates among people with substance abuse challenges remains high, creating a cycle that is unnecessarily expensive and harms the long-term health of communities, families and individuals. We must keep in mind the criminal justice system’s difficulties in addressing drug issues as we work to find solutions to our most recent substance abuse crisis: the decade-long increase in opioid abuse.

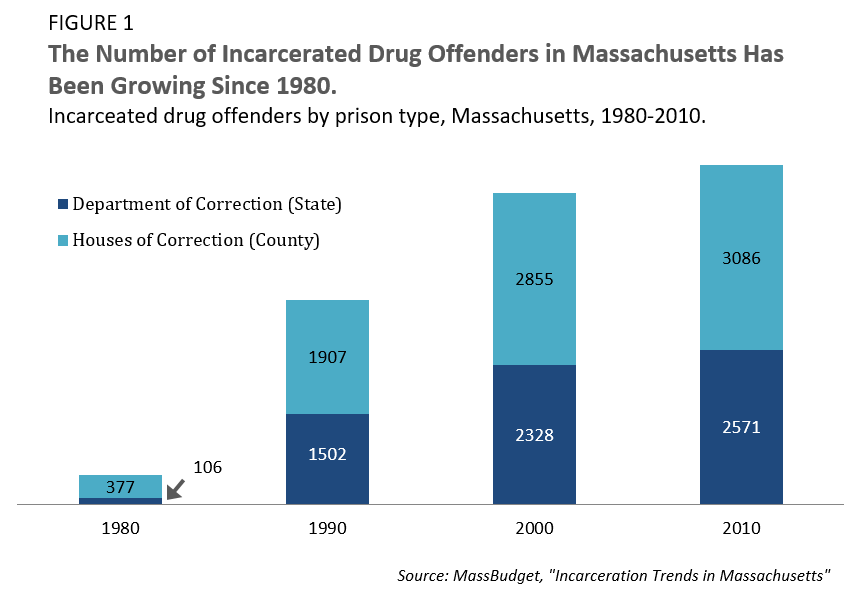

As part of a national move toward treating people with substance abuse problems as criminals who deserve harsh punishment, the number of people incarcerated for drug offenses in Massachusetts rose dramatically between 1980 and 2010. Specifically, according to a recent report from the Massachusetts Budget and Policy Center, we saw a tenfold increase in the number of drug offenders incarcerated in Massachusetts.

A note on our state’s prison system: Massachusetts has two types of prisons, county-run Houses of Correction and state-run Department of Correction facilities. Houses of Correction only incarcerate people with sentences up to 30 months while Department of Correction facilities allow for sentences of any duration, meaning they tend to house people with longer sentences. That said, the minimum state prison sentence is generally one or more years. People convicted of distributing or trafficking illegal substances are most often imprisoned in Department of Correction facilities, and those convicted of possessing illegal substances in small amounts are most often imprisoned in Houses of Correction. Both Department of Correction facilities and Houses of Corrections house pre-trial detainees.

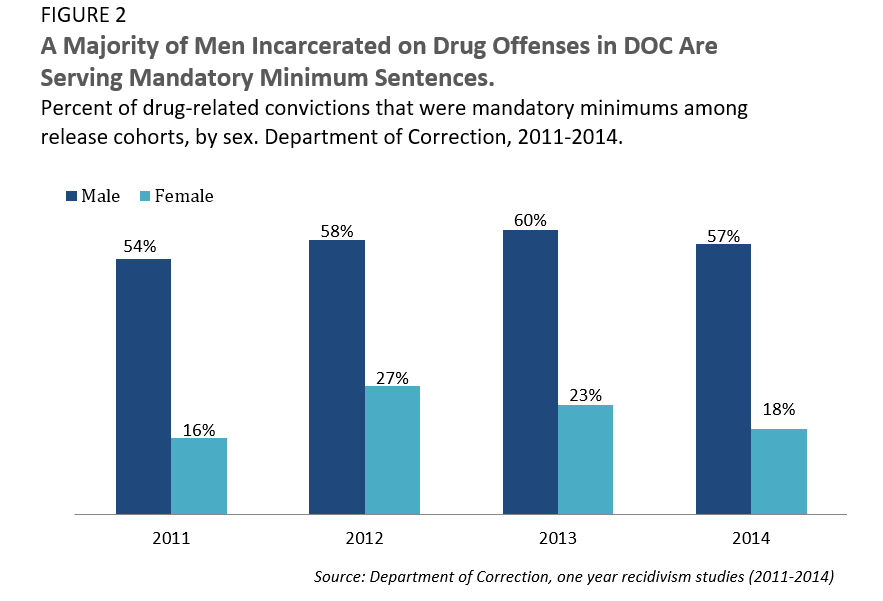

Mandatory minimum terms, which eliminate judicial discretion in sentencing, are among the key causes of our state’s increased prison population. As of 2014, 27 percent of men and 19 percent of women in Department of Correction facilities were convicted of drug offenses. Half of all of those incarcerated on drug crimes were serving mandatory minimum sentences.

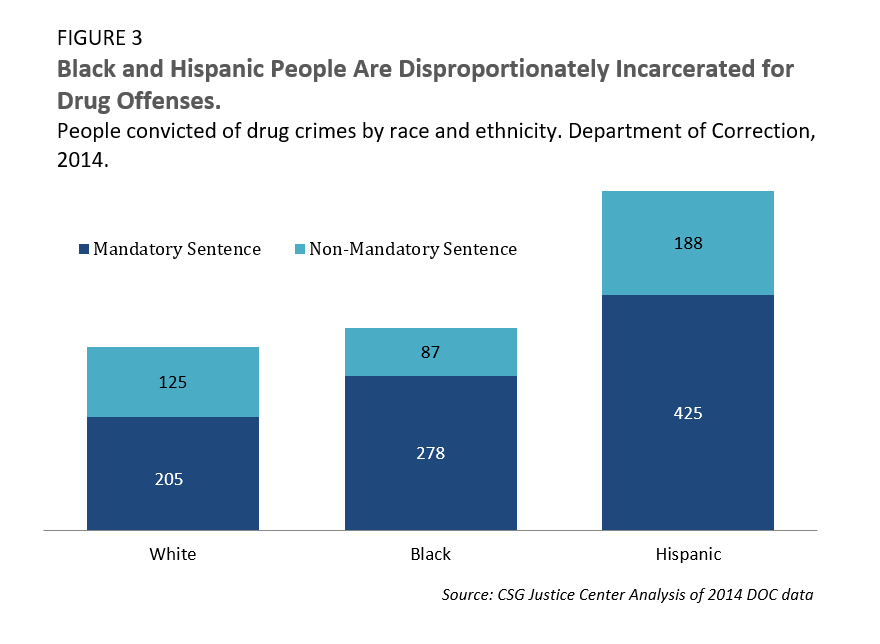

The application of mandatory minimums is particularly glaring among racial and ethnic minority groups. While Massachusetts’ total population is almost three-quarters white, about three-quarters of those incarcerated for drug offenses are black or Hispanic.

Although intended to ensure the safety of communities, little evidence exists to support the effectiveness of mandatory minimums. Research has shown that they have no consistently measurable effect on rates of crime—people are rarely deterred from committing crimes because of the threat of mandatory minimums. Furthermore, according to the Massachusetts Department of Correction, less than one in ten people incarcerated for drug offenses are serving concurrent sentences for violent crime. There are, without doubt, complex issues involving prosecution and over-sentencing of violent crimes that should be addressed. Independent of those issues, the data suggests that those incarcerated for drug offenses are mostly non-violent.

Treating Substance Abuse in Prison

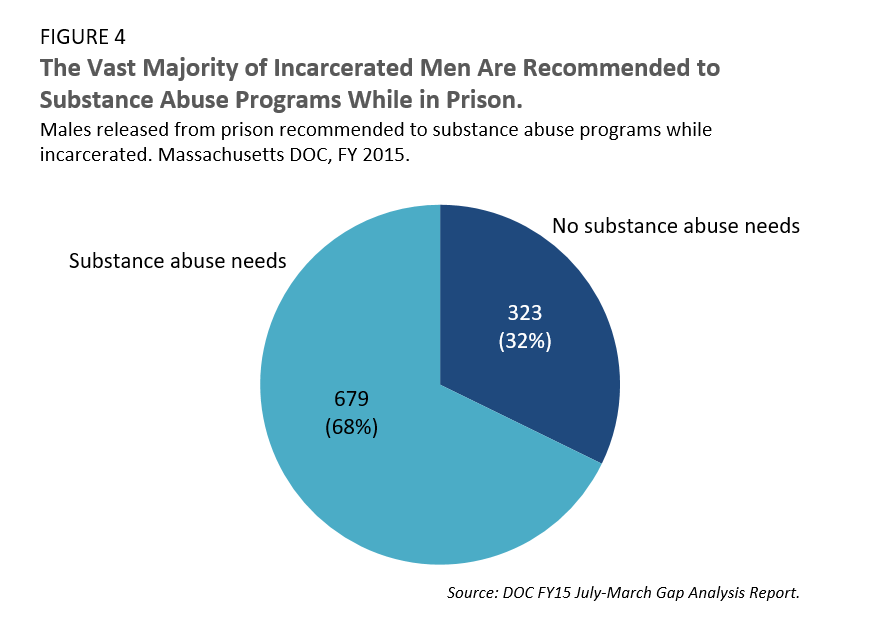

Among incarcerated men, substance abuse is widespread. The Department of Correction identifies three general areas for which prisoners might benefit from rehabilitation programming: substance abuse, criminal thinking and anger. Over two-thirds of incarcerated males have challenges with substance abuse and are eligible for substance abuse programs. By comparison, 47 percent are eligible for criminal thinking programs and 56 percent for anger management. (Due to limitations in available data, the information presented here refers only to people incarcerated in Department of Correction facilities. While data transparency could be greatly improved across both systems, data collection is much more uniform for the statewide Department of Correction than it is for the county-level House of Correction system. This said, recent analysis suggests that a vast majority of people incarcerated in Houses of Correction also have substance abuse histories.)

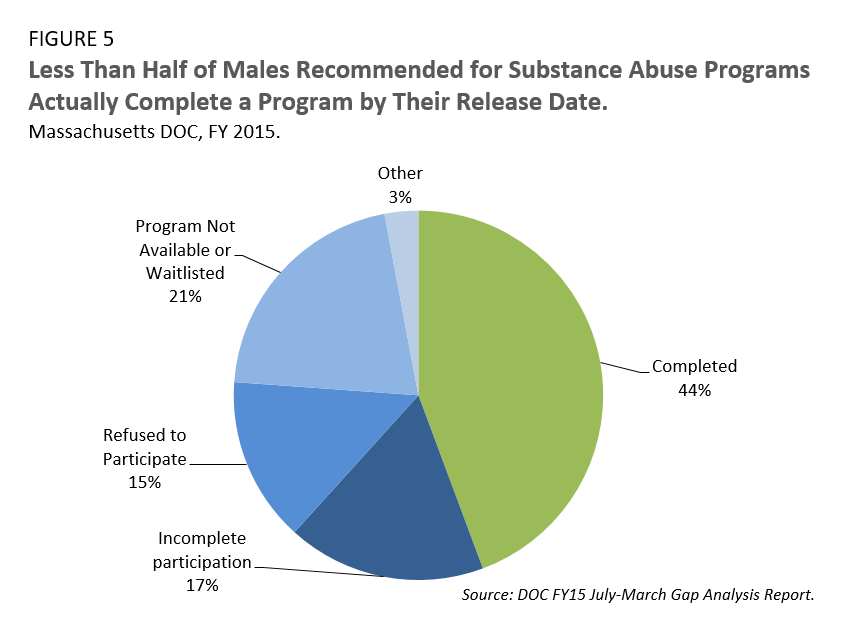

Of men recommended to substance abuse programs, however, less than half complete a program before their release date. While some simply do not want to participate, over 20 percent are either incarcerated in a location where substance abuse programs are unavailable or they remain on waitlists for programs that are already filled.

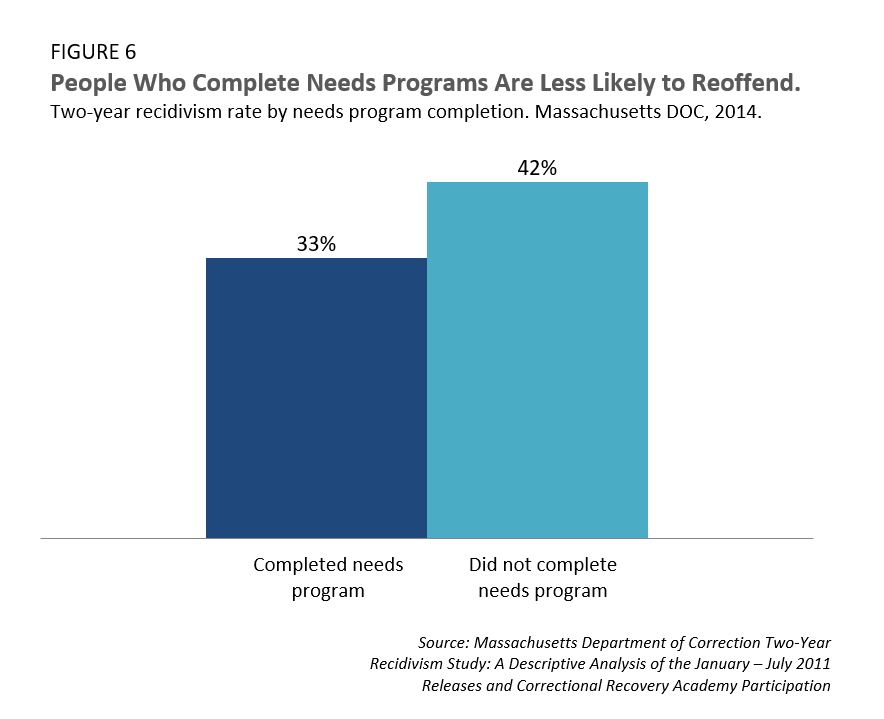

Program completion is particularly important because those who complete needs programs (inclusive of substance abuse, criminal thinking and anger programs) are less likely to commit crimes after they are released from prison than those who do not. In Massachusetts, 33 percent of those who completed a needs program reoffended while 42 percent of those who did not complete a program reoffended.

Rising Opioid Usage

While those who complete a needs program are less likely to commit additional crimes after they are released from prison, it’s worth noting that one in three who do complete a program still end up reoffending. Therefore, at its best our criminal justice system is still not succeeding at rehabilitating people convicted of crimes, especially drug crimes. This is worth keeping in mind as we wrestle with how to address our latest drug crisis, the opioid epidemic.

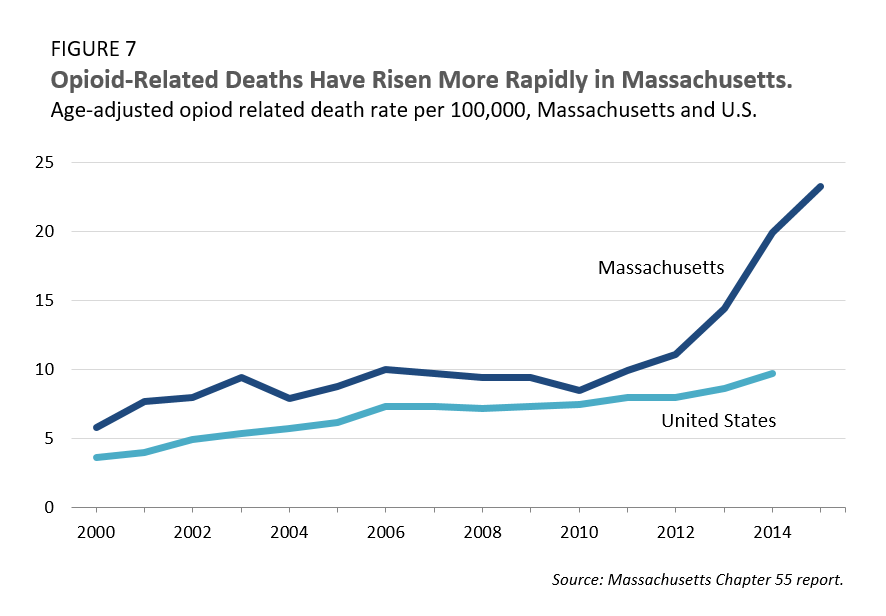

In the Commonwealth, the opioid-related death rate has quadrupled since 2000, according to the Massachusetts Chapter 55 report. Though we have seen recent progress - opioid-related deaths are down 10 percent in the past year - the long-term trend shows the Commonwealth’s opioid-related deaths far outpacing those of the nation. In 2014, for example, the opioid-related death rate (per 100,000 people) was 19.7 in Massachusetts compared to 9.7 in the country as a whole.

The opioid crisis is spread across the state, with particular concentrations in the Pioneer Valley, Southeastern Massachusetts and Cape Cod. Greater Boston is not immune to opioid deaths either—Medford, Malden, Revere, Chelsea and Quincy all have death rates above 20 per 100,000, more than double the national average.

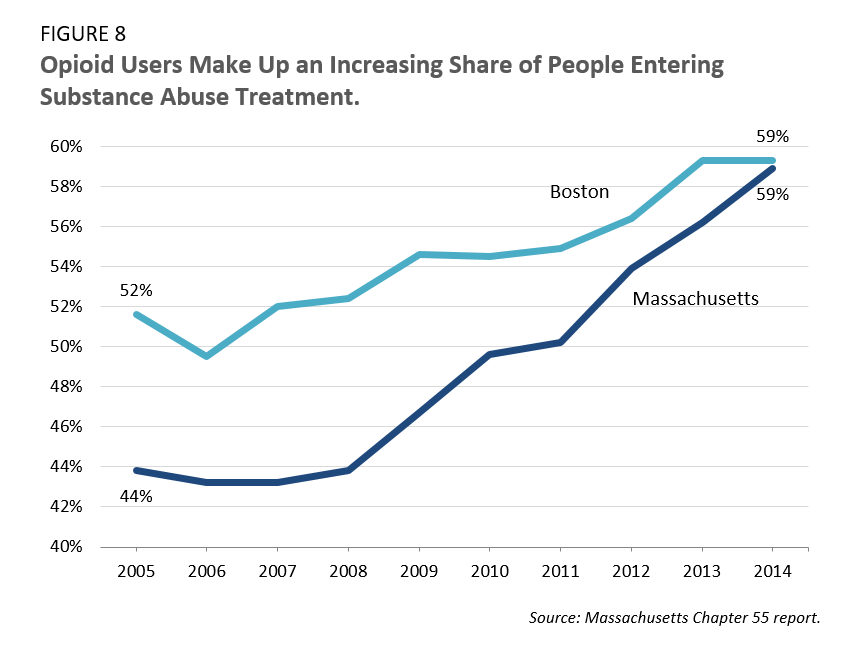

The growth in opioid usage is also captured in the share of those seeking substance abuse treatment for opioids. In Boston, the share of opioid users among all people entering substance abuse treatment has increased by 13 percent since 2005. Statewide, the increase is even more drastic—34 percent.

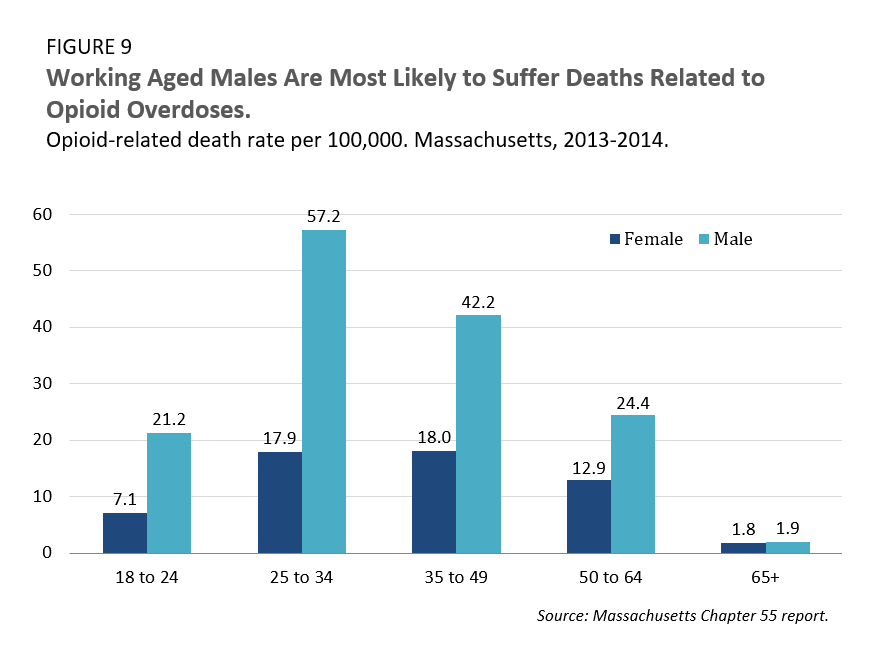

Working-age males have been particularly hard hit by the crisis. Men aged 25 to 34 have the greatest likelihood of suffering an opioid-related death, followed closely by men aged 35 to 49. While females do use opioids, males are more likely to experience an opioid-related death in all age groups except for those 65 and over.

Given our prisons' poor track record of providing effective substance abuse supports, the opioid crisis represents a challenge to our current criminal justice system. Housing more people with substance abuse needs in prisons already struggling to address the needs of current inmates seems unlikely to produce better results.

The Cost of Incarceration

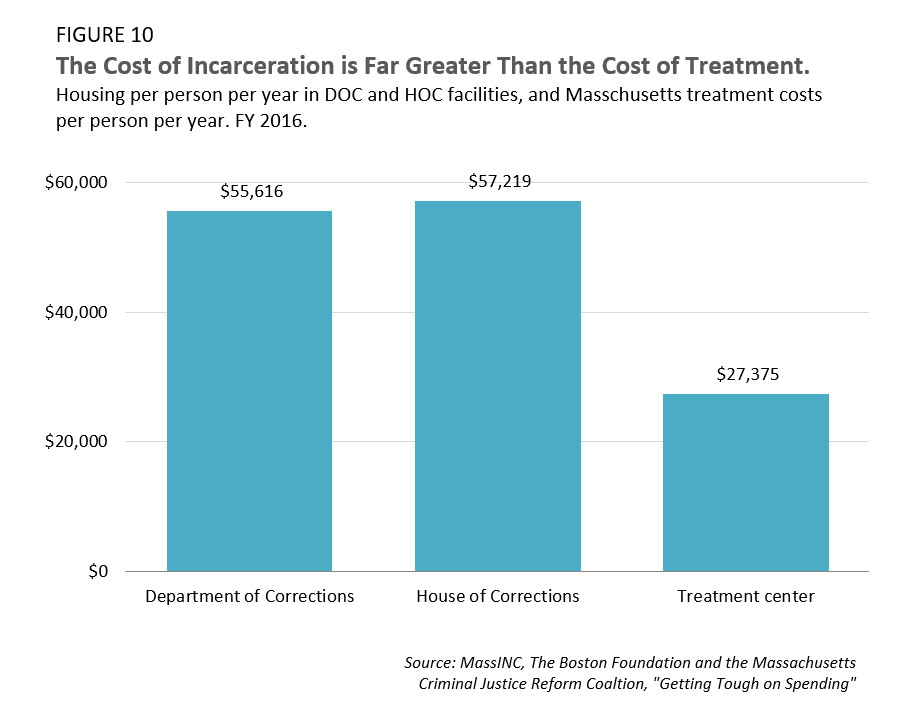

The yearly cost of housing one person in either a Department of Correction facility or a House of Correction facility is about twice as much as the cost to the state of treatment outside of prison. The higher cost of incarceration hardly ensures that a person with substance abuse challenges will remain outside of the criminal justice system, given the reasonable possibility of recidivism even with in-prison substance abuse programs.

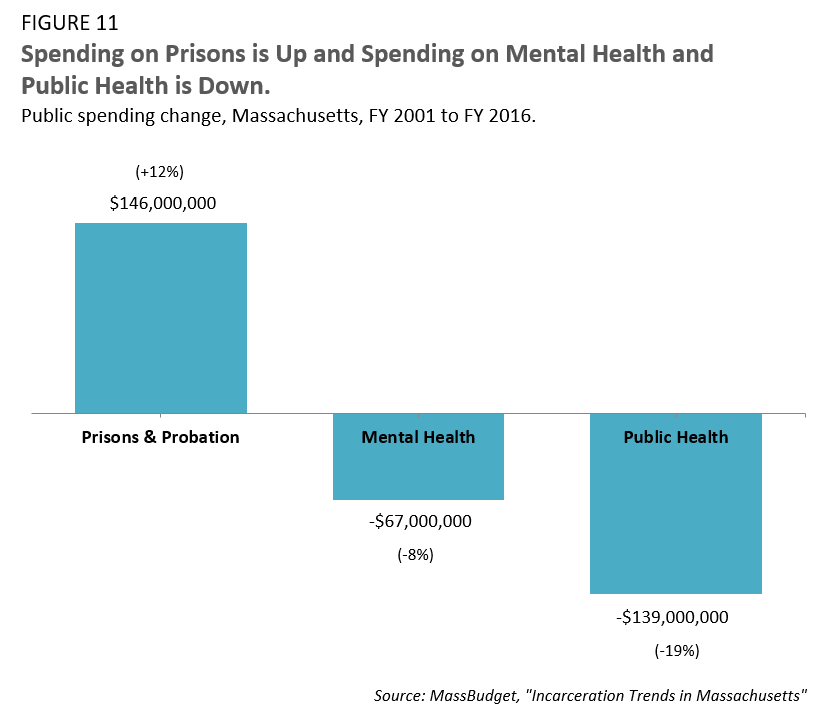

Public spending on prisons and probation has increased by 12 percent over the last 15 years. This increase is most striking when compared to trends in other areas. Spending on public health and mental health, for example, have decreased by 19 percent and 8 percent, respectively.

The connections between the opioid crisis and criminal justice reform are important to keep front and center as the state grapples with each issue. As people with substance abuse challenges cycle in and out of prison, we as a Commonwealth spend more to support a prison system that does not effectively address the disease of addiction. The savings that would be generated by incarcerating fewer people should be reinvested in addiction prevention and support programs that would better ensure the health and safety of our neighborhoods. And beyond these financial considerations, finding better strategies for addressing substance abuse would help break the cycles of addiction and incarceration that cause pain for families and communities statewide.