Who Is 'Some Other Race,' the Second-Largest Racial Group in Massachusetts?

By Luc Schuster

April 26, 2022

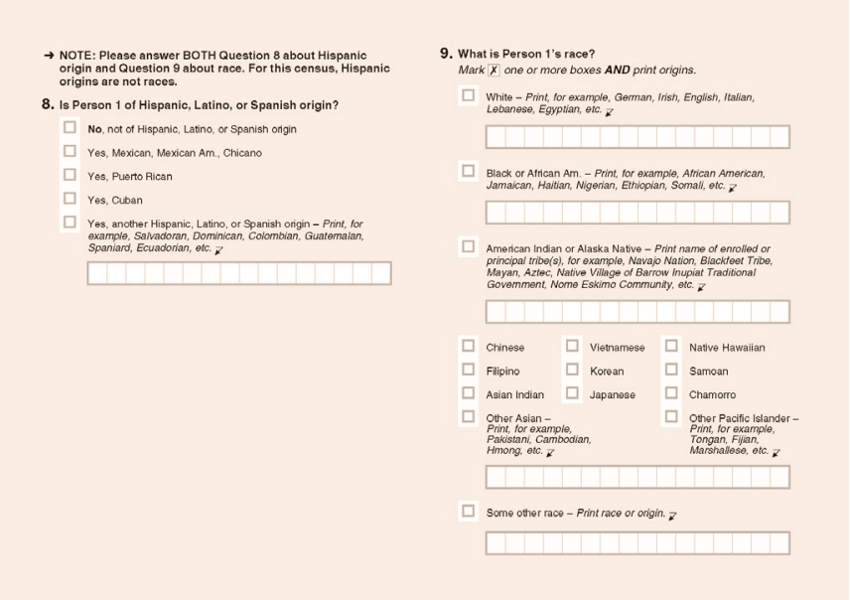

Among the most interesting findings from the 2020 Census is that Some Other Race has become the second-largest racial group in Massachusetts. The same is true nationally. Much of this change reflects growth among people of Latino ethnicity, who often select (or are assigned) Some Other Race. This overlap is driven by the Census Bureau’s two-question approach to asking about race separately from Latino/Hispanic ethnicity.

But Latino population growth does not explain the whole story. Many people simply do not fit Americanized racial categories, especially as new immigrants arrive from all corners of the world, and as families increasingly form across racial lines. So, who is “Some Other Race” and why is this group growing?

Who is Some Other Race?

While we don’t know precisely who is being counted as Some Other Race, there are a few common categories, including:

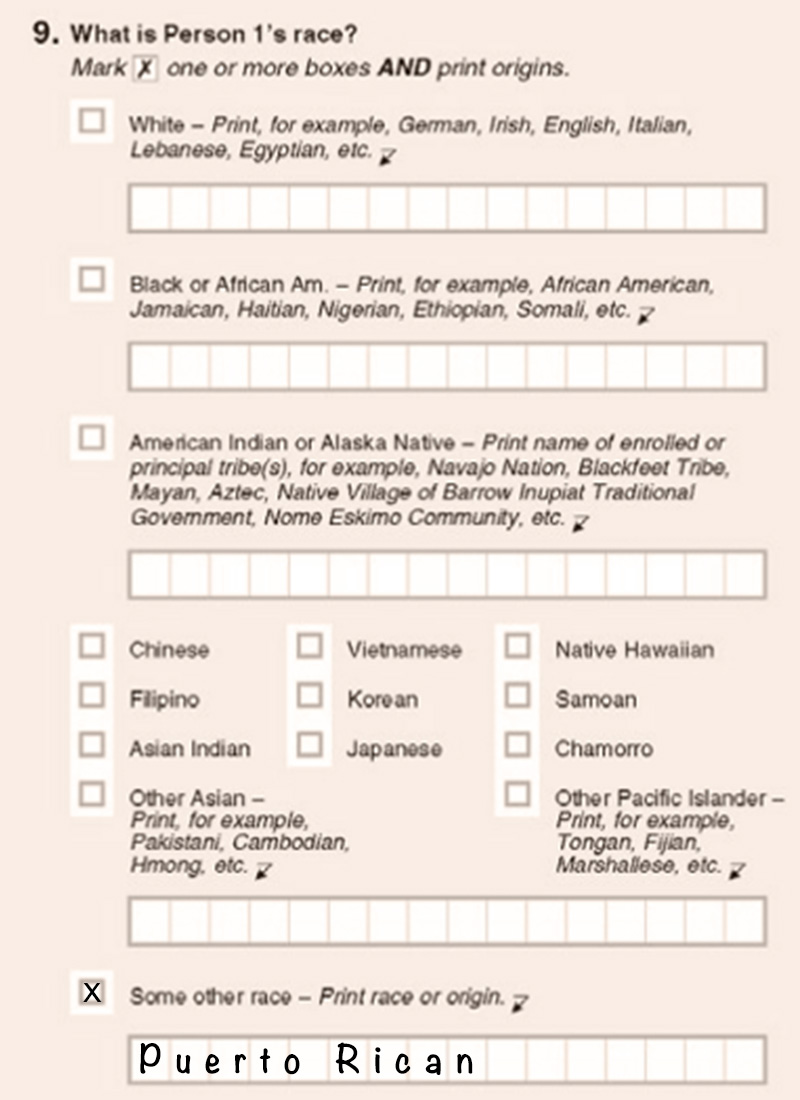

- Latinos. Since 1980, the census has included two separate questions on: 1) Hispanic or Latino ethnicity (or “Latino” for the rest of this brief); and 2) race. But in the United States context, most people treat being Latino as part of racial identity. This includes the vast majority of Latinos themselves—according to a 2015 Pew survey, 67 percent of Latino adults view being Latino as part of their racial background. So, when forced to select among the given race categories, 56 percent of Latinos in Massachusetts end up with Some Other Race (see graph below). Latin America is also quite racially diverse, so while many Latinos may be racially White, Black (i.e., Afro-Latino), or Indigenous (“Native American,” for census purposes), others have mixed (or “mestizo”) lineage and select Some Other Race.

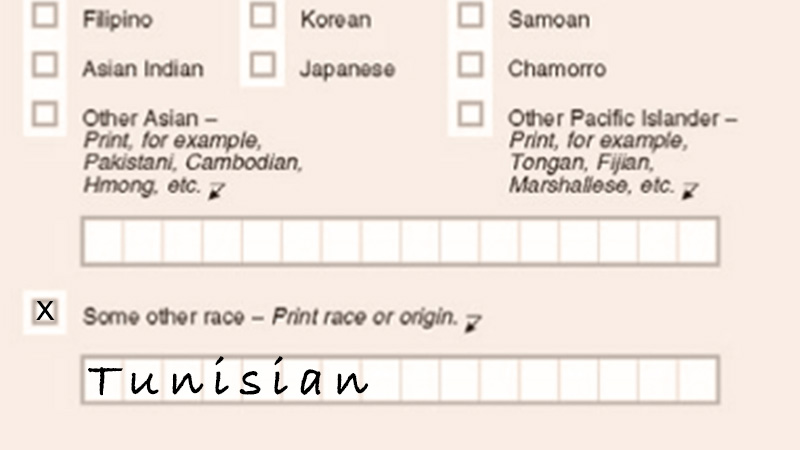

- People from the Middle East and North Africa. Some people don’t identify with any of the official racial categories or the Latino ethnicity option. Perhaps the most common instance of this is people from Middle Eastern or North African (MENA) countries, many of whom also identify as Arab. For now, MENA is not offered as a racial category, and the Census Bureau’s official guidance encourages people from these countries (e.g. Lebanon, Egypt, Iran) to select White. But many of these people do not view themselves this way and instead select Some Other Race.

Take, for instance, former Boston City Councilor and 2021 Mayoral candidate Annissa Essaibi George. The child of immigrant parents—her mother from Poland and her father from Tunisia—she spoke on the campaign trail about her frustration with the options provided to her by the census (see the race and ethnicity questions as printed in the 2020 Census below). She identifies as a woman of color and ultimately chose to write in an answer reflecting her Arab identity, presumably under the Some Other Race checkbox.

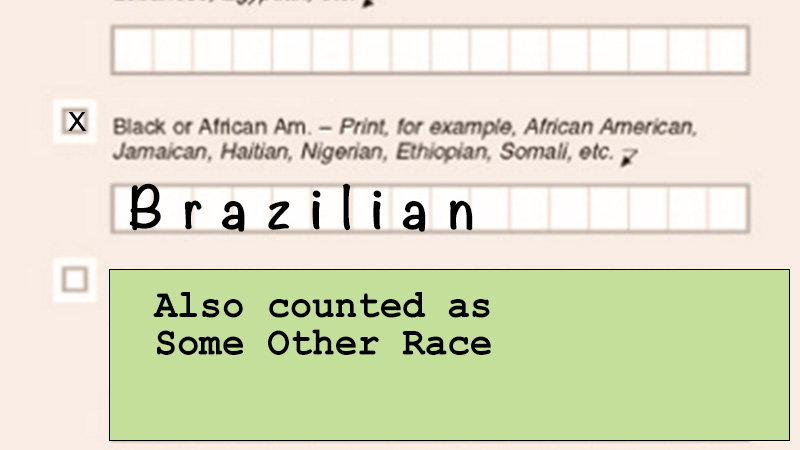

- People from a range of other, often smaller, countries that do not fit neatly into American racial categories. The Census Bureau officially considers people reporting a country of origin other than the United States to have a specific racial identity associated with that nation (see Appendix F in this document for these official categorizations). While races like Black, White and Asian have far more countries officially associated with them, the Census Bureau does list some countries of origin as officially “Some Other Race.” These include Brazil, Aruba, Belize, Bermuda, the Cayman Islands, Guyana, Surinam, and a few others. Brazilians are particularly noteworthy because, at more than 100,000, Massachusetts has the second-largest Brazilian population in the U.S. (after Florida). Because Brazilians are from Latin America, but not commonly Spanish speaking, there are differences of opinion over whether Brazilians should be considered of Hispanic or Latino ethnicity. For better or worse, the Census Bureau officially considers Brazilians not to be Hispanic or Latino. The article Who is Hispanic? from Pew Research Center has a useful discussion of these questions.

For many countries, the Census practice of associating individual racial categories with specific countries may seem straightforward—e.g., someone from Nigeria is considered Black and someone from China is considered Asian. But when you think about it, this logic breaks down quickly. The United States is far from the only nation of immigrants. According to current practice, the Census considers all people reporting French origins to be White and all people reporting South African origins to be Black. To the extent that racial categories are useful at all, it’s clear that many people hailing from those countries may well be of different racial backgrounds than the single official one designated by the Census Bureau.

- Other people who, for a variety of reasons, feel they don’t fit the official options. Even beyond the categories above, some people have mixed backgrounds and family lineages that make them generally uncomfortable with any of the official options. The journalist Alex Wagner writes about this in her opinion piece The Americans Our Government Won’t Count, where she says: “This ill-defined category (Some Other Race) is what mixed-race Americans, like me—half Burmese, half Luxembourgian-Irish—often check. It might as well be called ‘Generally Brown.’” Since 2000 respondents have been allowed to check more than one race box, but for some people selecting two or three official races still feels like an imprecise representation of who they are.

Why is Some Other Race growing?

-

There has been real population growth among groups that do not fit standard race categories, especially among Latinos. As any of the above groups grow, the number of people selecting Some Other Race increases, and many of them have in fact been growing. The Latino population, in particular, grew 41 percent in Massachusetts over the last decade, up from 627,654 residents in 2010 to 887,685 in 2020. And as part of a recent global wave of immigration, we’ve also experienced growth in residents from the Middle East and North Africa as well as from countries like Brazil.

- A back-end coding practice used by the Census Bureau accelerated the Some Other Race increase in 2020. The Census Bureau has adopted a back-end coding practice of assigning additional race selections to individuals whose write-in responses suggest different racial categories from the boxes they actually select. For instance, if a person selected White and wrote in Mexican below, the census counted their Mexican heritage as indicative of identifying with Some Other Race. So, in addition to being counted as Hispanic or Latino on the ethnicity question, this approach now leads some people with single Latino identities to be counted as multiracial—White and Some Other Race, using this example—even though these respondents do not actually choose two races. The logic for this practice is that it helps correct mistaken race category selections. But the downside is that it often simply overrides the self-identification of the respondent.

This became a much larger issue in 2020 because it was the first year for which there was a write-in box under the White and Black/African American checkboxes, instructing people to “(m)ark one or more (race) boxes AND print origins” in the write-in area. Ongoing Latino population growth combined with the importance of this back-end coding practice for 2020 is much of what’s behind the 129 percent increase nationwide in Some Other Race over the last decade, where it jumped from 21.7 million in 2010 to 49.9 million in 2020.

While this back-end coding practice changes the responses of Latinos most often, it applies to other groups as well. As mentioned above, for instance, the Census Bureau officially considers people from Brazil to be Some Other Race. So, if a person selects Black and then below that writes in “Brazil,” the Census Bureau counts this person as both Black and Some Other Race, even though the person never actually selected Some Other Race.

This has contributed to a large multiracial population spike for 2020 that is only partially explained by actual population growth among people who identify as multiracial. For more on the challenges that this presents for researchers aiming to track population change over time, see our 2021 research brief We're Reporting Census Data All Wrong.

Every U.S. census has included questions about race. As social norms around race, ethnicity, and identity have shifted over time, so too has the specific approach to asking these questions. But large changes haven’t been made in many years, and recently some researchers have been advocating for a new round of revisions. In 2015, the Census Bureau tested a revised approach that would have merged the two race and ethnicity questions into one, allowed for multiple responses, and added a new option for selecting Middle Eastern or North African. The Bureau found that this approach led to better information on people’s true identities and that it dramatically reduced the share of people selecting Some Other Race—down from 7 percent to 1 percent of the population.

Further, because MENA was a new option and because Latinos were not forced to select another racial category, this alternative approach would have also resulted in a lower White population total. This fact led to some countervailing political resistance. Some on the political right, resistant to America's growing racial and ethnic diversity, didn’t want to let go of these inflated White population totals. But some (although certainly not all) leaders of Middle Eastern or North African descent themselves resisted the addition of a MENA category out of fear that creating this new category could further “other” them in the American context. As we know, there can be real power in being considered White in America.

Ultimately, the Trump administration’s Office of Management and Budget, which had the final say over how the questions were asked, did not allow the Census Bureau to adopt this revised approach for 2020. For the time being, we are left with the current two-question approach, which is also used by the Census Bureau for the annual American Community Survey. The Biden administration has signaled an openness to consider a change, but it has not yet done so.

At the end of the day, there’s a limit to how precise a Census question on race could ever be. Race is a social construct based on categories that are imprecise, contested and ever-evolving. As the country’s foreign-born and multiracial populations grow, the lines between these categories blur even further. But getting these categories “right” is understandably high stakes in the American context, where racial categorization has been used for centuries as a tool for social and economic division. Some Other Race growing to become the second-largest race helps demonstrate the ongoing limitations of this approach to grouping people.