Who Still Believes? Local Trends in Religiosity.

By Peter Ciurczak

June 13, 2025

Over the past several years, Boston Indicators has conducted a range of research on the many identities that define our region. We’ve explored the region’s immigrant communities, its racial and ethnic diversity, and patterns shaped by income and age. But one dimension of identity has been missing from our work: religion. Faith can be one of the most deeply rooted aspects of a person’s identity and often intersects with ethnicity and culture. And at a time when concerns about social isolation and loneliness are rising, it’s worth considering how Boston’s religious landscape might be shifting and what role faith communities still play in fostering social connection.

We haven’t much looked at religion mostly because reliable local data have been scarce. But that changed with the recent release of new data from Pew’s Religious Landscape Study (RLS), a major national survey that captures a wide range of beliefs and practices. The RLS is Pew’s largest survey, reaching around 36,000 Americans in its latest wave (2023–2024), with earlier waves in 2007 and 2014. Its large sample allows for disaggregation at the local level.

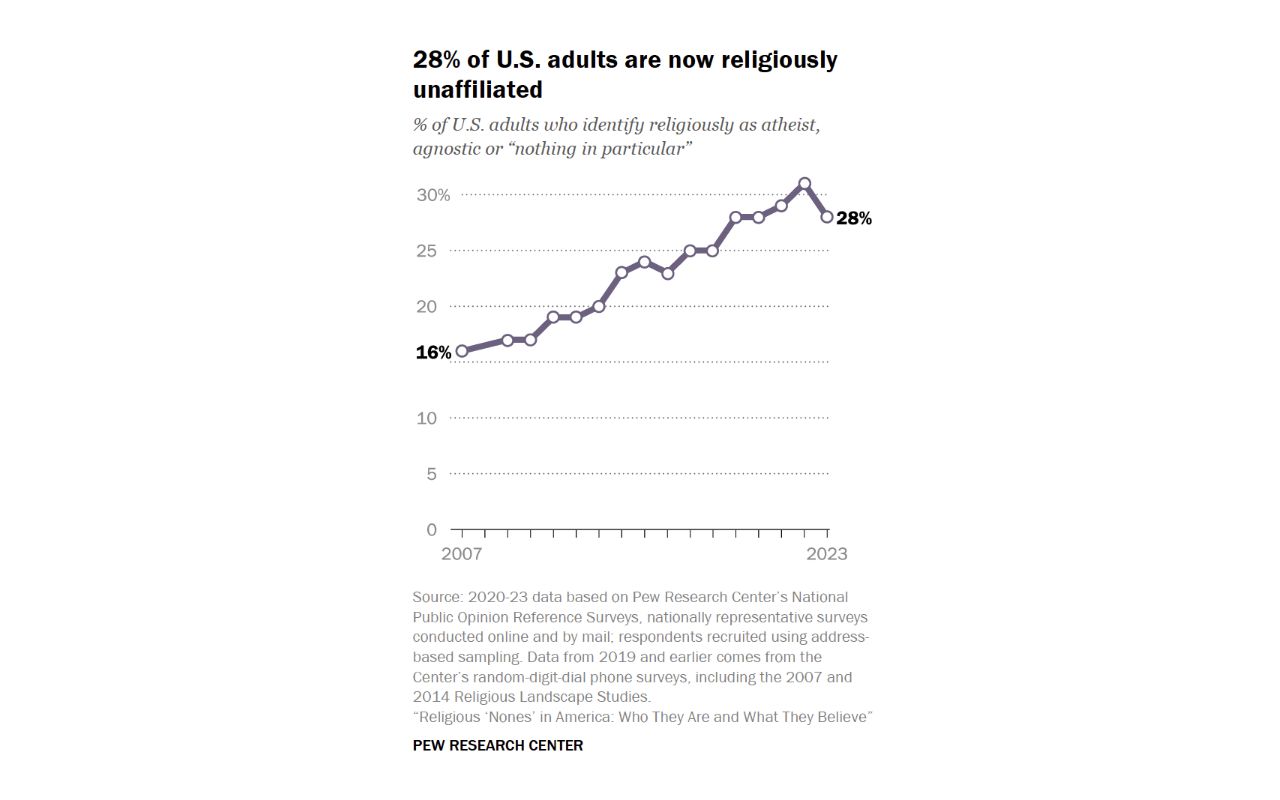

Nationally, the RLS data reflect a clear and ongoing trend: the steady secularization of American society. Between 2007 and 2014, the share of Americans reporting a religious affiliation declined from 83 percent to about 77 percent. Today, that figure stands at 69 percent, with Massachusetts slightly lower at 63 percent. Greater Boston stands out even more. In the most recent data, just 59 percent of residents report any religious affiliation, among the lowest rates in the nation. That marks a drop of 8 percentage points since 2014, and while we don’t have 2007 data specifically for Boston, the decline is likely even steeper given regional and national trends.

It’s worth noting that there is some evidence of a slowing down in the decline in religious affiliation over the past few years. Pew collects national affiliation data across two surveys, the larger RLS and the smaller National Public Opinion Research survey. And while both show declining religious affiliation, since about 2020 this decline has somewhat leveled out.

While unaffiliated adults make up just over a quarter of the population nationally, focusing on the 2023–2024 data and comparing across regions reveals stark local differences. In Greater Boston, about four in 10 adults are religiously unaffiliated. Among the nation’s largest metro areas, no other region comes close to that level.

Among those who are affiliated, most identify as Christian, and especially Catholic. This is likely a legacy of Boston’s strong Irish and Italian roots, along with more recent immigration from the Caribbean and Latin America. These new arrivals have helped sustain a Catholic share of 24 percent in the region, compared to just 19 percent nationally.

Boston also has a relatively large Jewish population. At 5 percent, it ranks behind only New York City and Miami among U.S. metro areas. Jewish immigration to Boston began as early as the mid-19th century, largely driven by Eastern European Jews fleeing poverty and persecution. More recently, Jewish immigration from the former Soviet Union brought highly educated newcomers, many of whom worked or still work in Boston’s tech, medical, and academic sectors.

When it comes to participation in religious services, Bostonians aren’t particularly reliable attendees. Data from the Census Household Pulse Survey suggest that while 53 percent of U.S. adults have not attended a service in the past year, that rises to 62 percent of adults in Greater Boston.

Interestingly, though, attendance varies sharply by race. Majorities of Black and Latino residents are likely to attend service at least once a year. In contrast, about 71 percent of White adults and 65 percent of Asian adults say they haven’t attended any services in the last year.

Beyond formal religious affiliation, it’s also important to understand how residents experience their faith. Many people are faithful and deeply spiritual without considering themselves religious. Pew’s Religious Landscape Study touches on some of these broader questions and points again to growing secularism.

In 2007, 56 percent of Americans said religion was "very important" in their lives. The survey didn’t ask respondents to clarify what aspect of their religion mattered most. For some, it may have been community connections built through a congregation. For others, a sense of closeness to God or a higher power.

Whatever the reason, religion’s perceived importance has declined sharply. In the 2023–24 data, just 38 percent of Americans say religion is very important to them. For Greater Boston, the number is even lower. Fewer than one in four residents say religion plays a central role in their lives, down from 36 percent a decade ago.

This lower sense of importance seems to extend to religious belief itself. Compared to both the national average and other large metro areas, Bostonians are less likely to believe in a personal God or universal spirit, the existence of heaven or hell, or the idea of a soul or spiritual force beyond the natural world.

This may partly reflect Boston’s high levels of educational attainment. Nationally, belief in these religious ideas tends to decline as education levels rise. While we don’t have detailed data on this for Boston, it would be surprising if the region—where more than half of adults hold a bachelor’s degree or higher—bucked this trend.

That said, higher education doesn’t always mean lower religious participation. In fact, nationally, adults with college or postgraduate degrees are just as likely to attend services regularly as those with lower levels of education. This holds especially true for Christians. In Boston, adults with postgraduate degrees are the most likely to attend a religious service at least once per year, according to the Household Pulse survey.

Still, skepticism of institutional religion remains. Despite the value religion holds for some, many Bostonians are ambivalent or even critical. About 27 percent of adults in the region believe religion does more harm than good, compared to 34 percent who believe it does more good. That 27 percent figure is higher than in any other large metro and above the national average.

Views like these are also correlated with education. Nationally, only 13 percent of adults with a high school diploma or less say religion does more harm than good. Among college graduates, that number rises to 24 percent, and among postgraduates it reaches 26 percent. As with other questions in the RLS, the survey does not clarify what people have in mind when they answer questions about “religion.” In Boston, where the Catholic Church sex abuse scandal was first exposed, the line between “religion” and “religious institutions” may be especially blurred.

Religious affiliation in Greater Boston has declined significantly over time, but there are still important ways in which faith communities remain vibrant. The region continues to have some of the largest Catholic and Jewish populations among major U.S. metro areas. And regardless of tradition, for many people, participation in religious life remains a source of support, friendship, cultural connection, and meaning, which may be increasingly hard to come by in modern times.