Authors

Sarah Crump, Research Assistant, Metropolitan Policy Program, Brookings InstitutionJenny Schuetz, Fellow, Metropolitan Policy Program, Brookings Institution

Trevor Mattos, Research Manager, Boston Indicators

Luc Schuster, Director, Boston Indicators

Editor

Sandy Kendall, The Boston Foundation

Designer

Kaajal Asher

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful for input and feedback from Soni Gupta, Director of Neighborhoods & Housing at the Boston Foundation; Amy Dain, Consultant at Dain Research; and Tom Hopper, Callie Clark and Lucas Munson at the Center for Housing Data at the Massachusetts Housing Partnership.

At its best, Greater Boston is a thriving region where we pair a strong economy with proactive government supports to help ensure opportunity for all, regardless of race or income. Housing is one area where we fall far short of this potential. Too many cities and towns restrict the dynamic functioning of the housing market by allowing construction only of large, expensive homes, and state and federal governments don’t do nearly enough to provide financial support to lower-income families. We can and must do better. Addressing these varied housing challenges will require a wide range of sustained solutions, largely along two paths: 1) building much more housing at price points accessible to moderate and middle-income families; and 2) providing significantly more public subsidy for low-income housing supports like the Massachusetts Rental Voucher Program and federal Section 8 vouchers. This paper proposes one big, yet also relatively simple, idea for helping on the home building front—legalizing apartments near transit.

The Big Idea in Brief

(organized by report section)

The Problems

- Residential Segregation. Greater Boston’s persistent residential segregation, both racial and economic, has been caused in part by legal prohibitions against the construction of diverse, lower-cost housing options like townhomes, duplexes and small apartment buildings (other causes include the practice of “redlining,” which prohibited many people living in lower-income neighborhoods of color from receiving federally-subsidized home loans). Suburban communities with some of the highest-performing public schools in the country, well-funded public infrastructure, and low rates of crime have used these housing prohibitions to effectively exclude many lower-income families and families of color from being able to live there. Half or more of the families living in places like Concord, Needham and Wellesley, for instance, earn more than $150,000 a year, and only about 10 percent or less of their populations are Black or Latinx.

- Housing Shortages and High Housing Costs. We have a growing regional economy that yearns for many more housing options at a wider range of price points. But we leave our most important housing policy decisions up to local governments that aren’t elected to meet our region’s shared needs. This mismatch of interests allows municipalities to ban most forms of new housing development through their local zoning codes. And now we have a massive housing shortage with costs rising as a result. Further, local planning meetings tend to be dominated by homeowners who are older, whiter and richer than the population at large, encouraging status quo opposition to new housing proposals. Fundamentally, the wrong level of government—small cities and towns, rather than the state—is making too many of our important housing policy decisions. This paper offers one concrete model for how the state can take a more proactive role in setting land use regulations that work for everyone (while still giving cities and towns lots of local leeway).

- Car Dependence and Climate Change. Banning modest multifamily housing development is one contributing factor (among many others) to climate change. Because we have artificially constrained the number of homes that can be clustered near train stations, more people commute to work alone in their cars than otherwise would. Immediately preceding the pandemic, road traffic was way up across Greater Boston, and it has already rebounded in recent months. Large single-family homes consume more energy to heat and cool, further contributing to climate impacts. People also increasingly prefer to live near amenities like schools, restaurants, and grocery stores, but more of these walkable downtown clusters won’t emerge if we don’t allow for modest new development around transit.

The Big Idea

- Adopt a policy legalizing low- to mid-rise multifamily housing (e.g., townhomes, duplexes, small apartment buildings), up to a maximum density of 20 units per acre, within one-half mile of all transit stations statewide. For shorthand, we refer to this proposed policy change as “legalizing apartments.” While we don’t include it as part of this proposal, station areas closer to the urban core could realistically support density levels that are even higher. Such a policy would level the playing field across localities, enabling property owners and developers to build the same structures under a common set of rules statewide.

The vast majority of residents living in suburbs that have banned multifamily housing likely do not consciously support the idea of using their local zoning code to exclude others. Amidst growing frustration that we as a country haven’t done more to advance racial and economic justice in recent years, undoing these housing bans provides a concrete opportunity to advance change at the local level.

The Impact

- Legalizing apartments near transit would help unlock access to many affluent Boston suburbs, adding socio-economic diversity. New condos in Wellesley Hills and Needham would be affordable to households earning under $100,000, for instance, well below the median income of current residents ($153,000 in Needham and $188,000 in Wellesley). Further, we estimate that the cost of building a new townhouse in Wellesley Hills is $826,000 and the cost of a new condo is less than $500,000—well below the median value of existing homes in Wellesley today (over $1 million).

- In Beverly, Melrose and Wellesley, the number of new condos that could be built within one-half mile of a single rail station over the next five years is similar or greater to total new housing built in the entire jurisdiction in the past five years. The town of Wellesley has permitted only 316 housing units between 2015 and 2019, 314 of which were single-family homes. The 290 multifamily condos that could be built near the Wellesley Hills station under this proposal would substantially expand and diversify the town’s housing stock.

- This proposal would take displacement pressure off of communities in Boston’s urban core and would create new rental housing available to lower-income voucher holders. In Wellesley and Needham, the monthly cost of new condos falls below HUD’s Small Area Fair Market Rents, meaning that households who receive federal housing vouchers could potentially rent condos in those communities.

- Allowing smaller, higher-density housing offers the greatest affordability improvements in the most expensive communities. In less expensive communities like Beverly and Melrose, newly built condos would not offer substantial savings relative to older existing homes. The advantage of a consistent statewide policy is that it enables new housing to be built in the places with highest demand, while lifting some market pressures from moderate-income communities that currently are providing most of the region’s new housing.

Case Studies: Examples of Statewide or Citywide Zoning Reform Initiatives

- Over the past two years, momentum to legalize apartments has grown across several states and localities. These efforts are aimed at reducing residential segregation and making moderate-cost housing more available. Notably, all successful zoning reforms have followed several years of campaigns dedicated to raising awareness of the issue and assembling diverse political coalitions in support.

Authors’ Note: The topics addressed in this paper—exclusionary zoning and high housing costs—are perennial problems in Massachusetts that long pre-date the COVID-19 pandemic and current economic slowdown. The pandemic has introduced new uncertainty about the demand for housing and transportation across the region in the short- and medium-term. Will demand remain elevated for housing outside of Boston's urban core? Will transit ridership remain low if work-from-home continues? Yet the current crisis has also highlighted the region's deep disparities in housing opportunities by race and income, which result directly from exclusionary zoning and its impacts on housing development. We believe that these problems will persist in some form absent targeted policy reform. The current moment challenges policymakers to plan for the region's long-term well-being, in addition to responding to the immediate crisis.

Housing insecurity in Massachusetts is not new, but the coronavirus pandemic has served to highlight its true extent. Entering the current crisis, home values across Greater Boston had risen 53 percent in just 10 years, according to the Federal Housing Finance Agency House Price Index, and two-thirds of low-income households (those in the bottom 20 percent of incomes) spent more than half their income on rent or mortgage payments. These pressing housing cost challenges are driven in large part by our region’s massive housing shortage. The rate of new housing construction has lagged job growth, putting upward pressure on prices and leading fewer households to move here for new opportunities. Using 2018 data from the American Community Survey on the number of housing units either occupied or available for rent or purchase, we estimate that Greater Boston would need an additional 39,000 units to achieve a “stable” vacancy rate (of 6 percent for rental units and 2 percent for ownership). Further, this baseline regional calculation almost certainly understates our true need for more housing. It doesn’t factor in all of the families that would have liked to move to Greater Boston had more housing been available, and it doesn’t account for projected population growth in the future.

Over-spending on housing leaves families unable to accumulate savings that would allow them to weather even temporary income losses due to emergencies—from personal crises like illness to public catastrophes such as the current pandemic. Indeed, the current public health crisis has been worsened by our existing housing woes. Many households live in poor-quality housing that can exacerbate respiratory health problems. Low-income families, especially those with children, are also prone to overcrowding—which has made it much harder to practice social distancing during the pandemic. For a virus that is spread primarily through close physical proximity, it makes sense that we’d see worse outbreaks in more densely populated cities, and this dynamic has been a topic of news coverage as the virus has spread. But the connection between overall population density (residents per acre) and positive case rates is actually not as strong as one might expect. Multiple people crowding into a given housing unit, on the other hand, is a more precise measure of people living in close proximity to other people, and this measure has a very strong association with higher COVID case rates, as shown in the graph below. Due to a legacy of systemic discrimination and structural racism, these lower-income communities are also much more likely to have large shares of Black and Latino residents.

The lack of access to affordable, decent quality, stable housing is most acute in metro areas like Boston, where strong labor markets increase demand for housing while restrictive local zoning laws artificially constrain the amount of housing that can be built. Specifically, wealthy suburbs across Greater Boston have adopted policies that prohibit the construction of anything other than single-family homes on large plots of land. By banning townhomes, duplexes and modest apartment buildings on most residential land, low- and moderate-income households have effectively been blocked from ever even contemplating moving to these communities.

This form of “exclusionary zoning” has funneled displacement pressure into the few cities near the urban core that do allow some multifamily development—like Boston, Cambridge, Malden and Newton. This leads most of our region’s intense debates around housing development, displacement and gentrification to occur in these communities. Meanwhile, many higher-income suburbs avoid these debates altogether because so few multifamily housing projects are ever even proposed.

Legal prohibitions against building anything other than single-family homes don't just hurt low- and moderate-income families. In the aggregate, dramatically limiting the availability of modest housing options leads to much higher housing costs region-wide, which in turn makes it harder for employers to hire and retain good workers.

Banning the construction of multifamily housing is especially problematic near public transportation because it causes more workers to undertake longer solo car commutes, thereby contributing to climate change and regional pollution. Greater Boston is fortunate to have a well-established commuter rail network that dots valuable train stations throughout all types of suburbs. But while the state built these valuable transit assets for the benefit of everyone regionwide, it has never required these beneficiary communities to allow multifamily housing to be built in close proximity to these stations. People live, work and play regionally and, yet, we haven’t done nearly enough to require all communities to contribute a baseline amount of accessible housing to help meet our shared housing needs.

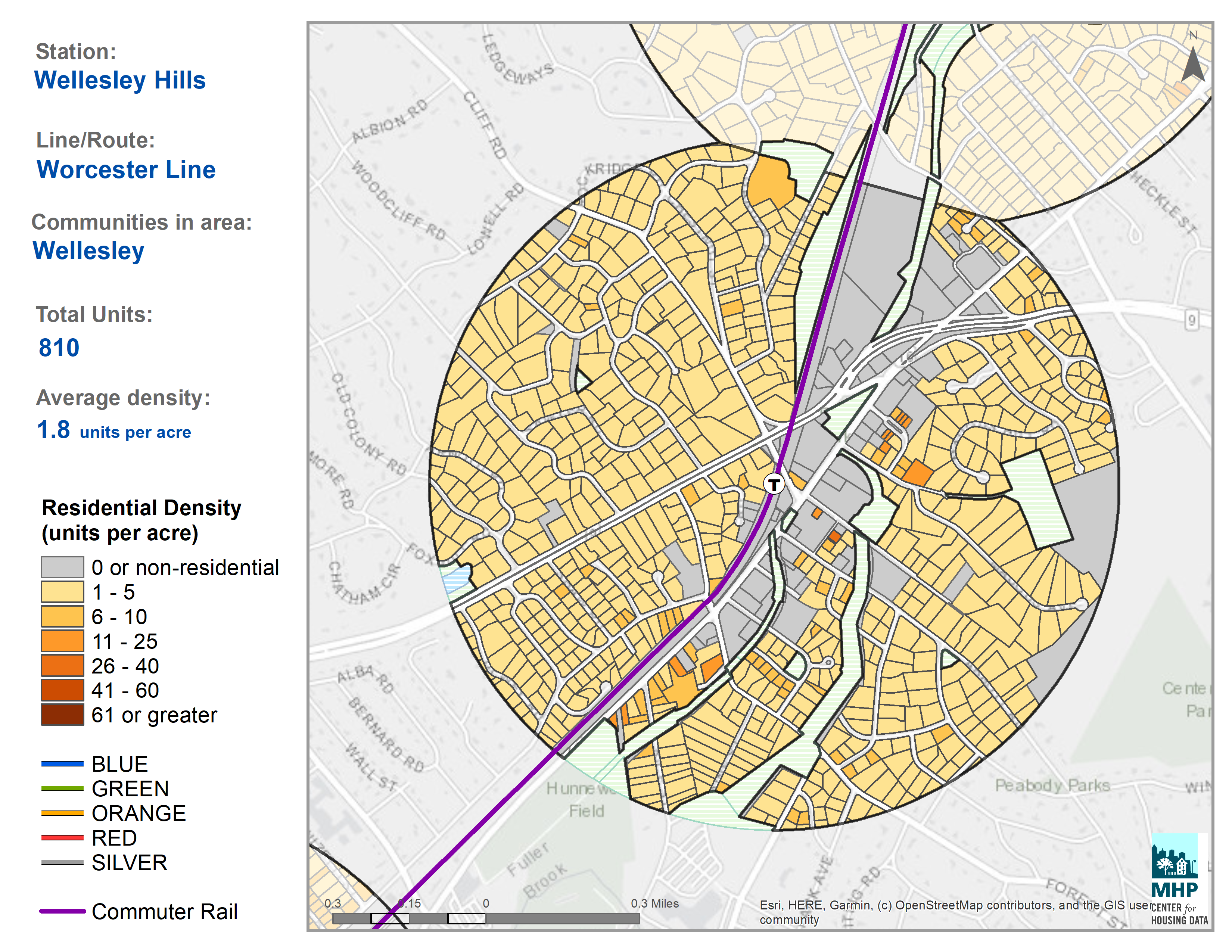

Through its interactive Transit-Oriented Development Explorer (TODEX), the Center for Housing Data at the Massachusetts Housing Partnership has created an invaluable database for analyzing the current state of housing production near transit across Greater Boston; they find that median housing density around all Commuter Rail stations is a meager 2.8 units per acre. While this density may be appropriate for a select few or the most remote stations areas, huge numbers of these stations are within close proximity to job centers and desirable downtowns.

Later in this paper we provide case studies and model potential new housing development for four sample station areas, but to show what these current housing patterns look like for one of these station areas, below we show a map for the ½ mile area surrounding the Wellesley Hills Commuter Rail station. This neighborhood is less than 15 miles from downtown Boston, and the train takes commuters to Back Bay in Boston in less than 30 minutes at the height of rush hour. There’s a small downtown along Washington Street with a few older apartment buildings. But here’s the kicker: The town of Wellesley has made it illegal to build anything other than single-family homes on the vast majority of the land in this neighborhood. Current density for the full neighborhood is only 1.8 units of housing per acre.

Below is a Google satellite view of what these housing patterns actually look like in practice. The Wellesley Hills station is marked by the red pin. Immediately south and east of the station there is some commerce and a few small apartment buildings. But this moderate density land use is only on one side of the station, and even on that side it lasts for only a couple of blocks. Contrast that with areas to the north and west, where there are relatively large yards, a few scattered single-family homes and basically no multifamily structures. The select few people who do live here are living on tremendously valuable, transit-proximate land; they can roll out of bed minutes before their scheduled departure time and still make it to work in downtown Boston within 30-45 minutes.

Below are a few examples of individual single-family homes each within two blocks of the Wellesley Hills train station. We show these not to point fingers at individual homeowners—anyone living here now is living in the only type of housing allowed by law—but to help people who may not be familiar with these higher-income suburban areas better visualize what’s currently there. Having such large single-family homes located right next to public transit represents a massive failure of regional planning. This is one cause, among many others, of our regional housing crisis.

This is not to say that we shouldn’t have neighborhoods like this in Greater Boston; it’s just unfortunate that so much of the land within a stone’s throw of mass transit stops is dedicated to sparsely-populated housing patterns like these. As we show later in this paper, allowing for modest housing density on large lot sizes like these could lead to the construction of many more housing units, at significantly lower cost, for a region that desperately needs more available housing.

It’s also important to note that legalizing moderate-density housing is far different from eliminating single-family homes. Property owners could absolutely keep their homes as-is. It would just give owners the option of redeveloping land so that more families could live in close proximity to transit and small downtowns, if they chose to do so. Our current approach, by contrast, actually does eliminate townhomes, duplexes and modest apartment buildings. Undoing single-family-exclusive zoning would just make them an option in places where there’s market demand.

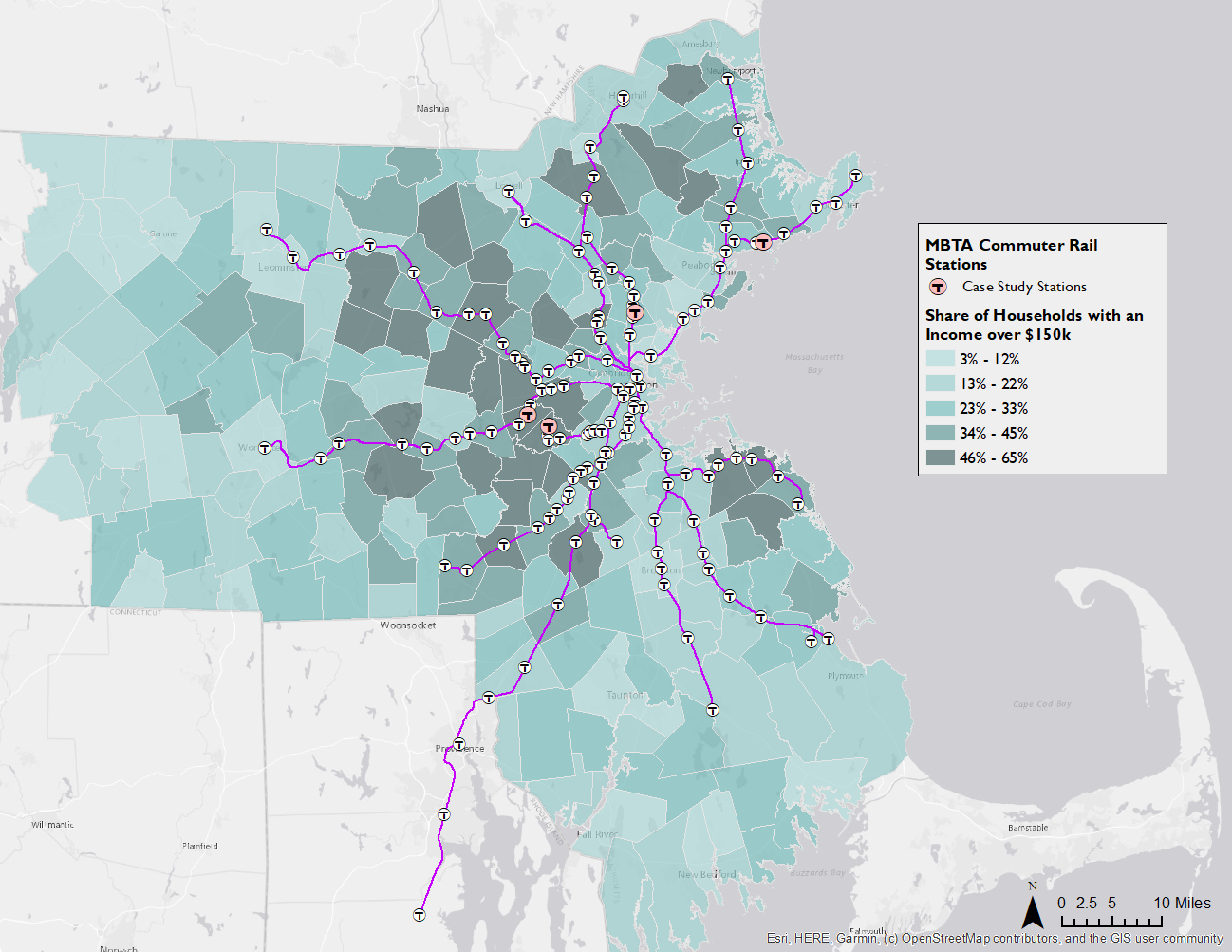

The current pandemic is also revealing the social and economic costs of residential segregation created in part by these terribly uneven residential development patterns. Some cities have large populations of unstably housed and homeless people, whereas others are predominantly home to households with much higher income incomes. The following maps provide a few ways to visualize our region’s current patterns of residential segregation. First we look at income segregation, showing the share of higher-income households in a given city or town earning more than $150,000 a year (for context, median household income for Greater Boston is about $80,000 a year). In some suburbs west and north of Boston more than half of all households earn above this $150,000 level.

Most of the highest-income communities (in darker shades of blue) are outside of the urban core immediately around Boston but are still within a 15- to 45-minute train ride into the city. Lower incomes tend to emerge again when you get out towards the end of many of the commuter rail lines, in Gateway Cities like Lowell, Fitchburg and Worcester.

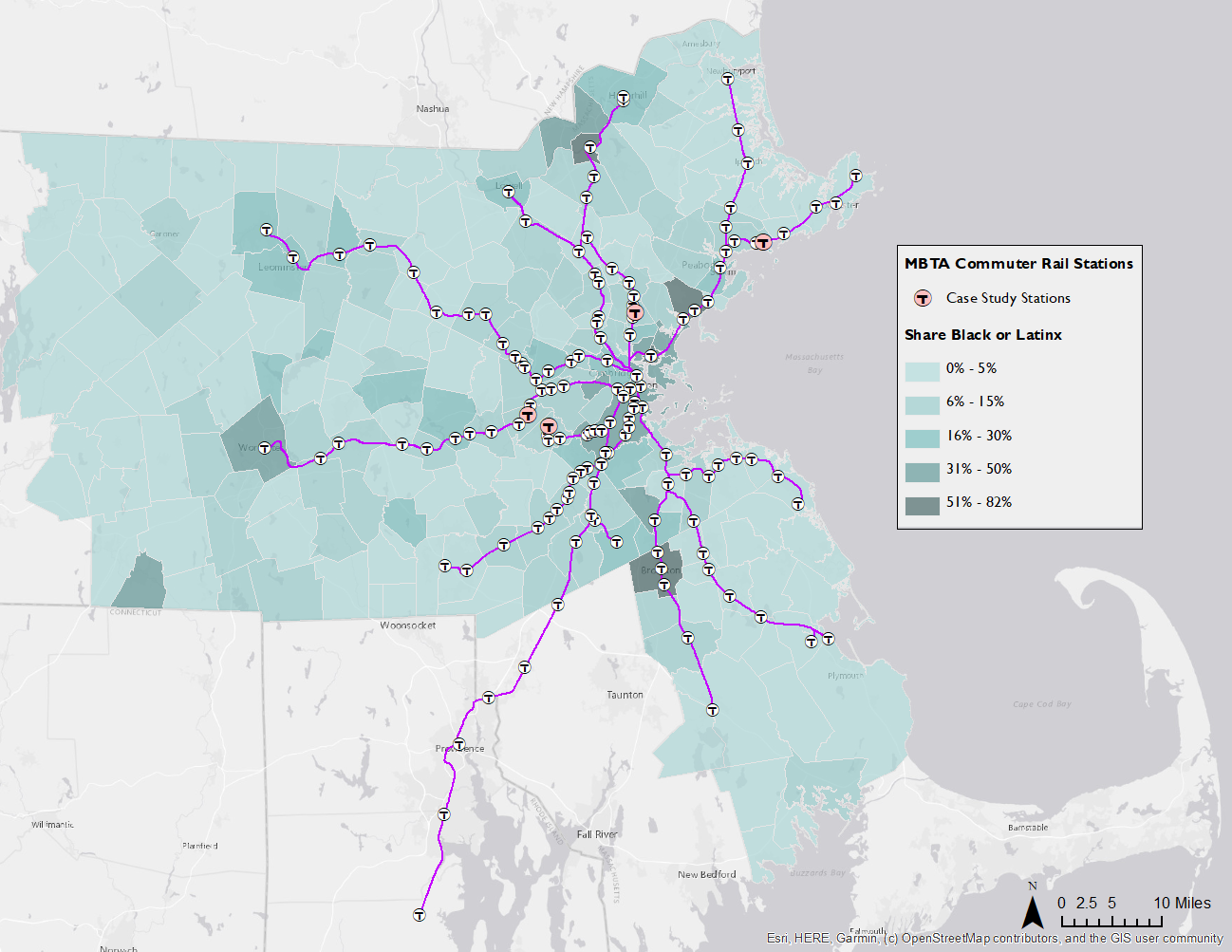

Because of the close relationship between race and income, it’s not surprising that we see similar patterns when mapping residential patterns by race. In the below map we look at the combined Black/Latino population share of a given city or town. We see large clusters in Boston and some urban suburbs paired with very low Black/Latino shares in western suburbs. Again, when you get out toward the end of Commuter Rail lines much further from the urban core, some the combined Black/Latino population shares increase again.

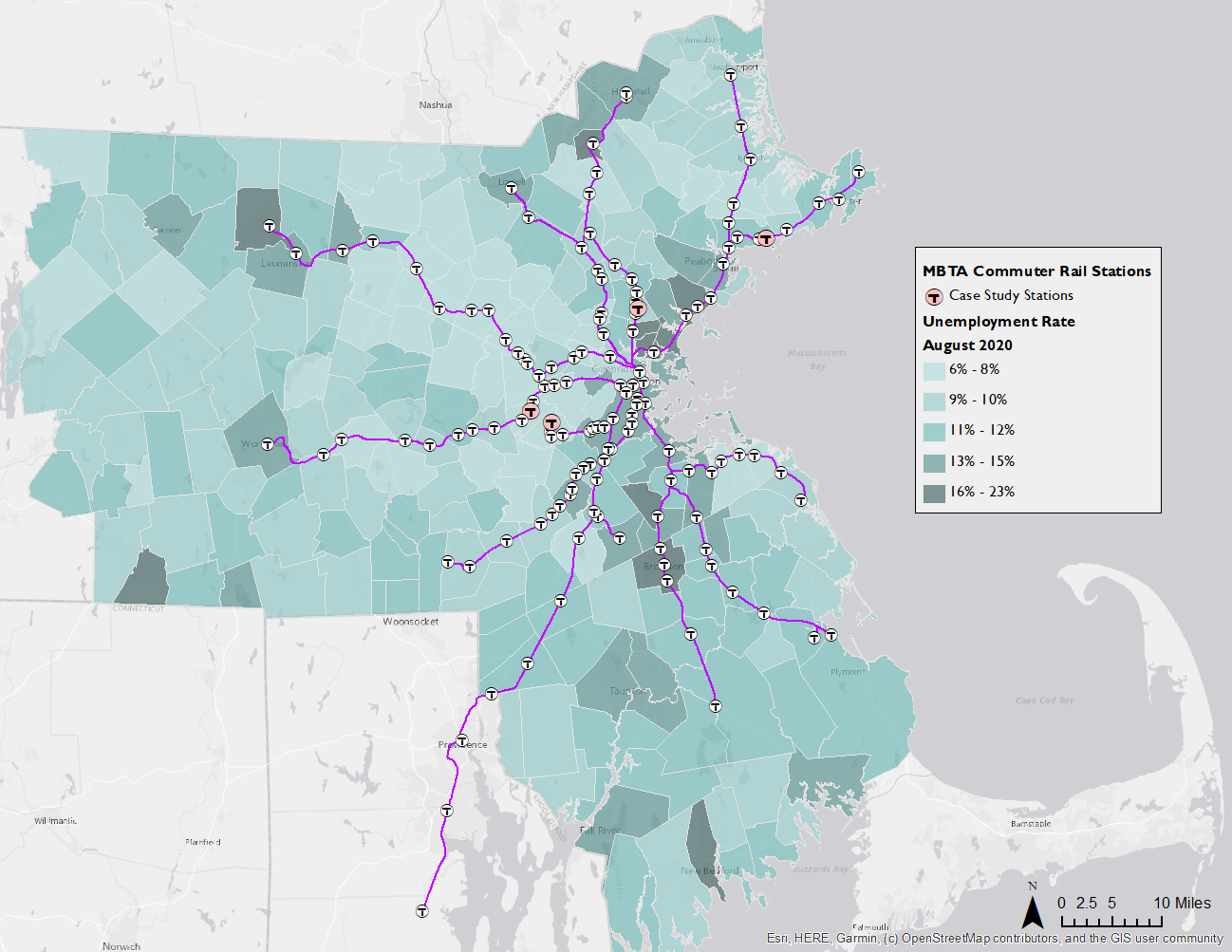

Finally, below we map local unemployment rates near the peak of the COVID crisis’s economic collapse in July of 2020. In communities like Lawrence, Brockton and Chelsea, roughly one in four workers was unemployed as of July, whereas some higher-income suburbs along the commuter rail still had unemployment rates below 10 percent. This uneven distribution of unemployment helps explain why some communities have felt so devastated by the pandemic’s economic effects while others have largely gone untouched.

We propose a statewide policy to allow moderate-density multifamily housing—including duplexes, townhouses and low-rise apartments—within one-half mile of all transit stations. Such a policy would level the playing field across localities: Property owners and developers would be able to build the same structures under a common set of rules in areas immediately adjacent to the state’s mass transit system. For shorthand, we refer to this proposed policy change as “legalizing apartments.”

Currently, local governments across Massachusetts block apartment development through three types of regulations.

- Zoning laws can directly prohibit multifamily structures from being built, by specifying that only single-family detached homes are allowed.

- Zoning sets dimensional requirements—such as minimum lot sizes, lot widths, building height or setbacks—that may make constructing apartments physically or financially infeasible. For instance, setting a maximum building height of two stories does not outright prohibit apartments, but in practice would limit most new construction.

- While single-family homes can generally be built as-of-right, most local governments in Massachusetts impose additional procedural requirements for multifamily housing. For instance, obtaining permission for apartments often requires an extensive community engagement process, allowing current residents of the jurisdiction to voice their opposition to the project. These procedural hurdles increase the costs and risks associated with building apartments, and effectively delay or deter many projects.

To ensure that the state policy change effectively eliminates barriers, it is essential that local governments not be able to block development through any of these back-door channels.1

The diversity of existing housing and land use patterns around transit stations raises some challenges in how to define a statewide zoning policy that is consistent but also flexible enough to work in many different locations. Legalizing low- to mid-rise housing, up to a maximum density of 20 units per acre would allow moderate-density apartments around most suburban commuter rail stations, as we demonstrate in our analysis. But many station neighborhoods in the urban core are already developed at or above those thresholds. To allow and encourage substantial amounts of infill redevelopment around those stations would require a second, higher density threshold.2 Our analysis focuses on neighborhoods around suburban commuter rail stations, because these areas offer the greatest potential gains from an economic and racial equity lens. If policymakers want to pursue a comprehensive statewide pro-housing policy, it would be worth exploring how to design a multi-tiered approach, with greater density allowed near the urban core, and perhaps a different set of guidelines for high-frequency bus stations, both of which are outside the scope of our current analysis.

Our analysis illustrates how legalizing apartments could enable infill redevelopment near suburban commuter rail stations by converting parcels currently used as single-family homes into moderate density multifamily. Many communities that were originally developed for middle-income households, but which have seen rising land values over time, experienced a gradual process of “mansionization,” in which small, older single-family homes are demolished and replaced with much larger, more expensive single-family homes. If these areas were zoned to allow multifamily housing, the redevelopment process could replace older single-family homes with multiple apartments—increasing the total housing supply in those communities.

Allowing housing markets to build new housing in places with high demand is one strategy to reduce the pressures of gentrification and displacement in lower-income communities. Currently, the most affluent communities in Massachusetts effectively bar most new housing development. That pushes new housing into more permissive communities—including lower-income, Black and Latino neighborhoods.

We examine what that process would look like for four representative station areas that vary by current housing density and cost: Beverly Farms, Melrose Cedar Place, Needham Heights and Wellesley Hills. We estimate how the cost of newly developed housing would compare to existing homes in each community and how much additional housing could be built. For each station area, we examine three redevelopment scenarios: newly built single-family detached houses, attached single-family houses (townhouses), or low-rise multifamily buildings. The next section provides more details on the methods used in our analysis.

We focus on one specific form of redevelopment—converting individual parcels from single-family to small multifamily buildings—for three reasons. First, these conversions create additional housing in small-scale buildings that fit the existing neighborhood context, and so are less disruptive to residents. Second, it avoids the costly and time-consuming process of assembling multiple land parcels, allowing housing to be built quickly and at lower cost.3 Third, small-scale projects are more feasible and appealing for small, locally-owned development firms, rather than the deep-pocketed national companies that dominate apartment construction in large cities. Our proposal would also enable developers to build larger multifamily and mixed residential-commercial projects on large land parcels or by converting non-residential uses to housing. Because these projects are usually quite idiosyncratic and take much longer to complete, creating detailed financial models is considerably more complicated and therefore outside the scope of this analysis.

Finally, the design of a statewide policy to encourage moderate-density development would also need to consider regulatory and institutional barriers to housing other than zoning. Some communities have widespread use of historic preservation that limits the ability to demolish or alter existing structures, including those surrounding rail stations. A number of communities lack complete water and sewer systems, relying instead on wells and septic systems, which are more difficult to scale up for apartment buildings. We do not discuss how a statewide zoning pre-emption could successfully address these challenges, but note that this is an area requiring further study.

1 There are several mechanisms Massachusetts could use to legalize apartments. The state could delegate permitting authority for transit-adjacent areas to a state agency, which would be responsible for writing appropriate zoning and approving permit requests. Alternately, the state could establish a “builder’s remedy” similar to Chapter 40(b). If a local government denies a proposal to build apartments near a station, the developer can appeal to a state administrative agency. The state could also pre-empt local governments from prohibiting apartments outright near transit stations, from imposing discretionary procedural rules, or from adopting dimensional requirements that would make multifamily buildings infeasible. The most straightforward way to do this is to establish a consistent set of requirements that establish a minimum baseline for what type of housing is allowed near stations. Local governments would be free to adopt regulations that allow or encourage higher density than the state baseline, of course.

2 Some jurisdictions in the urban core have downzoned land so that structures currently built are above the allowed density, and therefore could not be rebuilt to their existing size. A statewide upzoning would enable some development that is currently illegal, depending on how the policy was designed. We discuss further examples in the Impact section.

3 Researchers have documented how the need to assemble large land parcels is an expensive and lengthy process, especially prone to individual owners “holding out” for higher prices (Brooks and Lutz 2016).

Underlying the analysis is a core tenet of urban economics: In places where land is expensive, developers will choose to use smaller amounts of land per housing unit. Since the 1970s, cities and towns across Massachusetts have largely banned apartments and other forms of dense housing, impeding this basic market mechanism from helping address our housing needs. Building smaller homes on smaller lots or stacking homes vertically is the most economically efficient way to build on expensive land. This holds true in predicting where there is greatest demand for redeveloping single-family homes into apartments: Neighborhoods with high land values and low-density housing offer the greatest financial opportunity to add housing, and in turn the largest improvements in affordability.

To understand how a statewide legalization of moderate-density housing near rail stations would impact local and regional housing markets, we seek to answer three questions:

- Will legalizing apartments make it financially feasible for developers to redevelop land surrounding stations?

- What are the affordability implications of higher density redevelopment?

- How much additional housing could be constructed near stations by redeveloping existing lots at a higher density?

Our analysis proceeds in four stages. First, we select four station areas that are representative of suburban neighborhoods with varying potential for redevelopment: Beverly Farms, Melrose Cedar Park, Needham Heights and Wellesley Hills. Second, for each station area, we model the financial costs of redeveloping existing single-family lots into either new single-family houses, attached townhouses or low-rise condominiums. Third, we analyze how newly built housing would affect affordability in our sample communities. Fourth, we simulate how many additional housing units could be built within the half-mile radius of each station area.

Key results of our analysis indicate that:

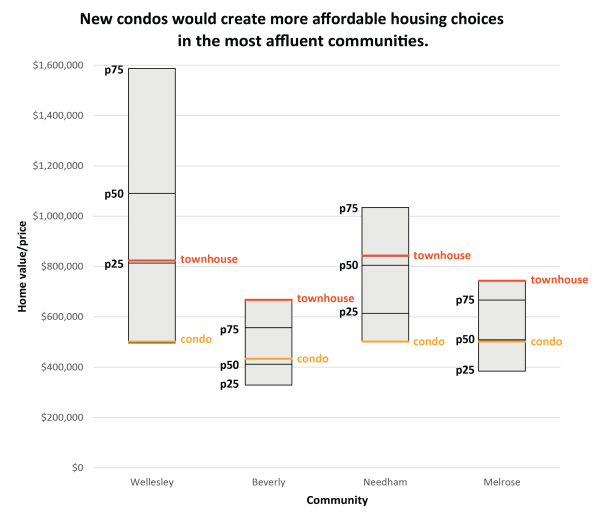

- Redeveloping single-family lots with townhouses or small multifamily buildings could substantially improve affordability in affluent, expensive communities. In Wellesley Hills, the cost of building a new townhouse is $826,000 and the cost of a new condo is less than $500,000—well below the median value of existing homes in Wellesley (around $1 million).

- Building smaller, lower-cost homes in affluent communities would allow households who currently cannot afford to live in those communities an opportunity to move there, adding socio-economic diversity. New condos in Wellesley Hills and Needham would be affordable to households earning under $100,000, well below the median income of current residents ($153,000 in Needham and $188,000 in Wellesley).

- In Beverly, Melrose and Wellesley, the number of new condos that could be built within one-half mile of a single rail station over the next five years is similar or greater to total new housing built in the entire jurisdiction in the past five years. The town of Wellesley has permitted only 316 housing units between 2015 and 2019, all but two of them single-family homes. The 290 multifamily condos that could be built near the Wellesley Hills station would substantially expand and diversify housing stock in the community.

- In Wellesley and Needham, the monthly cost of new condos falls below HUD’s Small Area Fair Market Rents, meaning that households who receive federal housing vouchers could potentially rent condos in those communities.

- Allowing smaller, higher-density housing offers the greatest affordability improvements in the most expensive communities. In less expensive communities like Beverly and Melrose, newly built condos would not offer substantial savings relative to older existing homes. The advantage of a consistent statewide policy is that it enables new housing to be built in the places with highest demand, while lifting some market pressures from moderate-income communities that currently are providing most of the region’s new housing.

How we selected Commuter Rail station areas with capacity for additional housing.

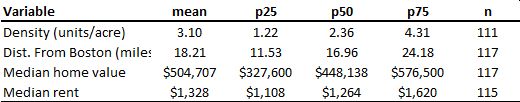

The two most important factors that affect the feasibility of redevelopment are existing housing density and housing values. Therefore, we want to choose station areas that vary along these two dimensions to conduct financial modeling.

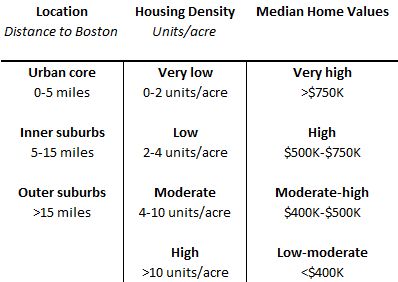

Starting with the 117 Commuter Rail station areas, we group them into several categories based on location, density and housing prices.4 We eliminate from consideration station areas that are currently developed at moderate to high density (over 10 units/acre), and those with low-to-moderate housing values, because these stations are least likely to support redevelopment. The parameters of our proposal were chosen to reduce barriers to development in suburban jurisdictions that have been most resistant to contributing to our state’s housing needs, so therefore we exclude stations within five miles of downtown Boston. Although many of the closer-in stations could also accommodate additional housing, the existing housing stock and land use patterns in those neighborhoods are quite different, so would require a separate analysis. Based on the distribution of stations by initial housing density and housing values (see Table 1), we identify four categories of stations that are prime for redevelopment and of most interest for financial modeling.

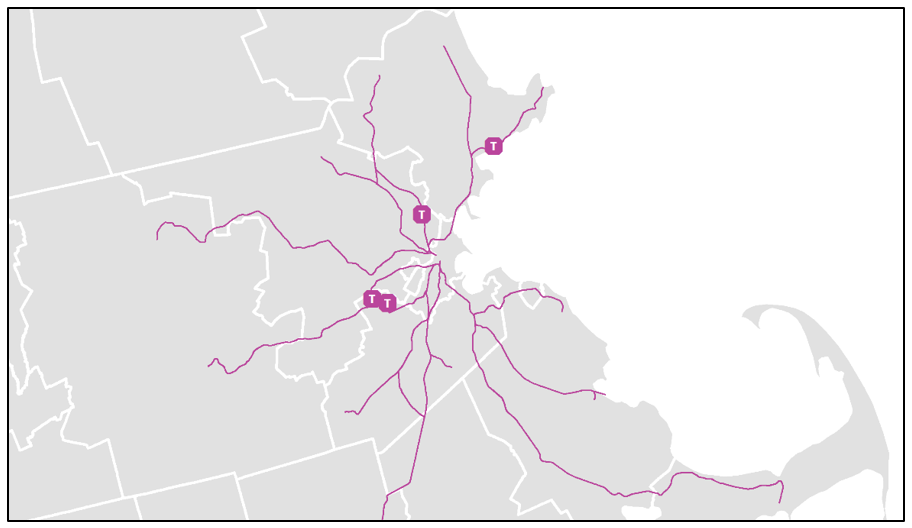

Within these four categories, we also consider qualitative information on whether there are idiosyncratic features that could inhibit redevelopment. As described in the previous section, a straightforward zoning pre-emption would not address barriers such as historic preservation districts or incomplete water and sewer systems. Furthermore, some stations are adjacent to large institutional landowners like universities. Based on these considerations, we selected four station areas that present relatively straightforward opportunities for redevelopment. Shown in Figure 1, these are; (1) Wellesley Hills, (2) Needham Heights, (3) Melrose Cedar Park and (4) Beverly Farms. More information on the current land use of these stations and others throughout the region is available through the Massachusetts Housing Partnership’s TODEX Explorer.

Locating the Four Selected Commuter Rail Stations in the Greater Boston Region

Note: Station Locations obtained from Massachusetts Housing Partnership's TODEX explorer.

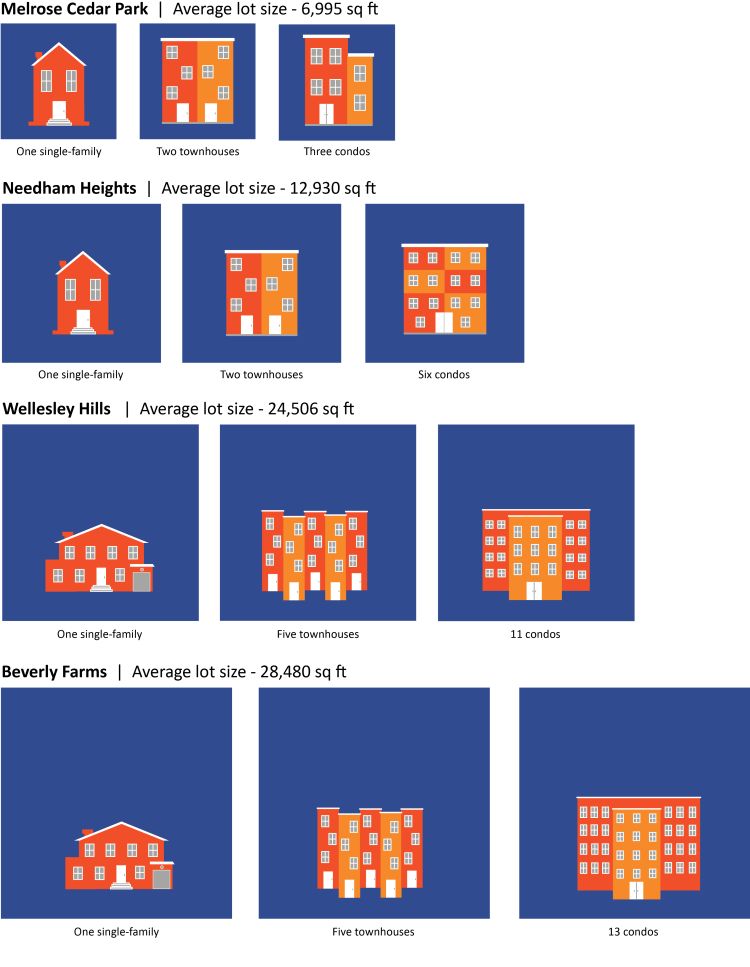

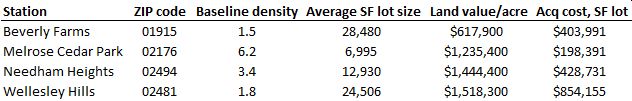

The selected station areas are quite affluent and have high housing values. The initial housing density and average lot size vary quite a bit, which has important implications for the number of housing units that could be built per lot under a statewide upzoning. As shown in Table 2, Melrose Cedar Heights has the smallest residential lot size of the four neighborhoods, just under 7,000 square feet.

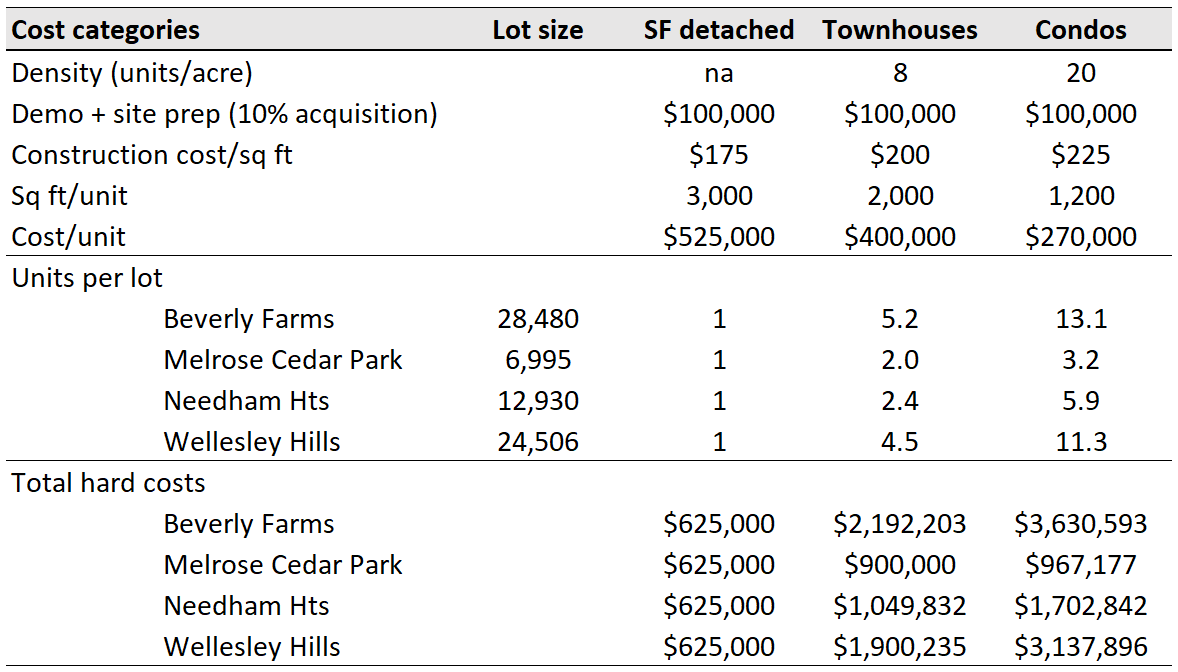

As the Big Idea section discussed, how a statewide policy change would impact housing markets depends on what types of structures and maximum densities it would allow. To explore how these details matter, we chose two different structure types and densities to model: townhouses (attached single-family structures up to 8 units per acre), and low-rise multifamily buildings (maximum density 20 units per acre).5 To put these numbers in regional context, the West Medford station area currently has housing density of about 6.6 units per acre. Englewood Avenue station in Brookline has a density of about 25 housing units per acre. Both station areas are surrounded by mostly low-rise structures (under six stories).

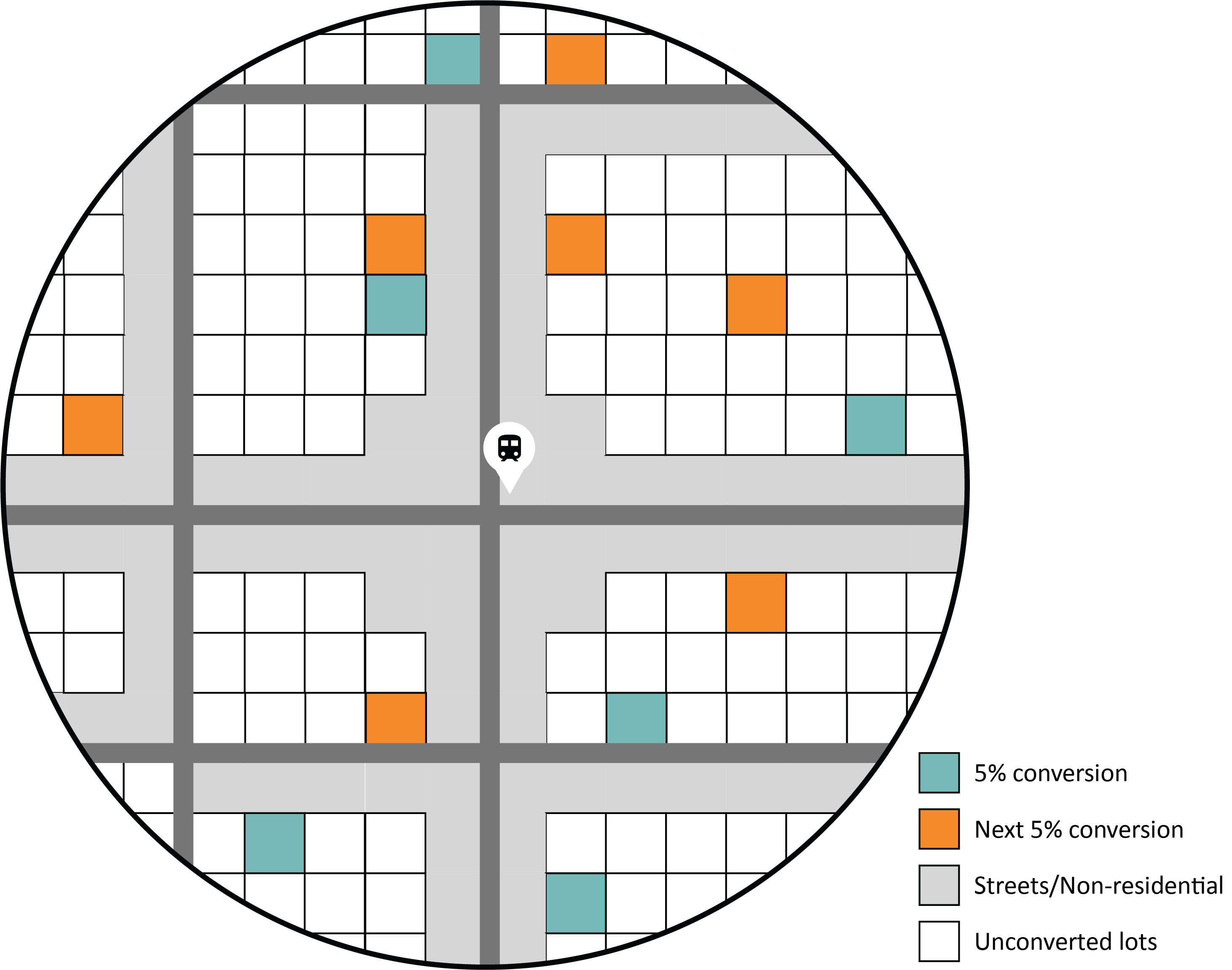

Figure 2 shows the relative size of typical single-family lots at each station area, and what those lots would look like redeveloped as either townhouses or moderate-density multifamily buildings. The typical lot in Melrose Cedar Park could fit two side-by-side townhomes (or a stacked duplex) or a three-unit condo building (similar to triple-deckers elsewhere in the Greater Boston region). The typical single-family lot near Beverly Farms is around 28,000 square feet, or roughly two-thirds of an acre, and could fit five side-by-side townhomes or 13 condo units.

Financial analysis of redevelopment

Whether a statewide upzoning will effectively result in more housing being built depends on the financial returns to redevelopment. How much would it cost for a developer to purchase a parcel of land and build townhomes or multifamily condos on that parcel? Would the sale price of newly built housing be enough to cover those costs, including the developers’ required return?

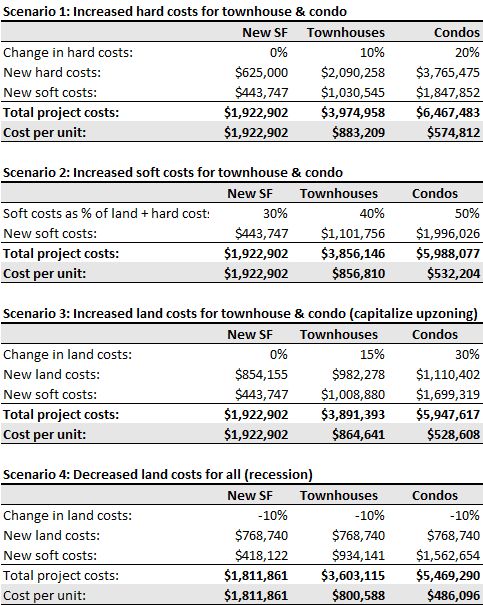

To answer these questions, we conduct cash flow analysis (called a pro forma) for developing three different structure types at each of our four station areas. There are three primary components to development costs. Land acquisition is the cost of purchasing an existing piece of land. Hard construction costs include labor and materials. “Soft” costs include architecture and engineering fees, financing costs, and developer fees. Appendix Table 6 provides a more detailed breakdown of each of these categories and sources of our cost estimates. The data set used in our analysis pre-dates the COVID-19 crisis, because that is the most recent available. There is considerable uncertainty in how the pandemic and recession will impact housing markets in the medium to long term. In addition to the primary estimates shown below, we ran several scenario analyses varying key inputs to the model, with both increased and decreased construction costs and land values (see Appendix Table 7). The main results are qualitatively consistent in these scenarios, although the specific numbers vary.

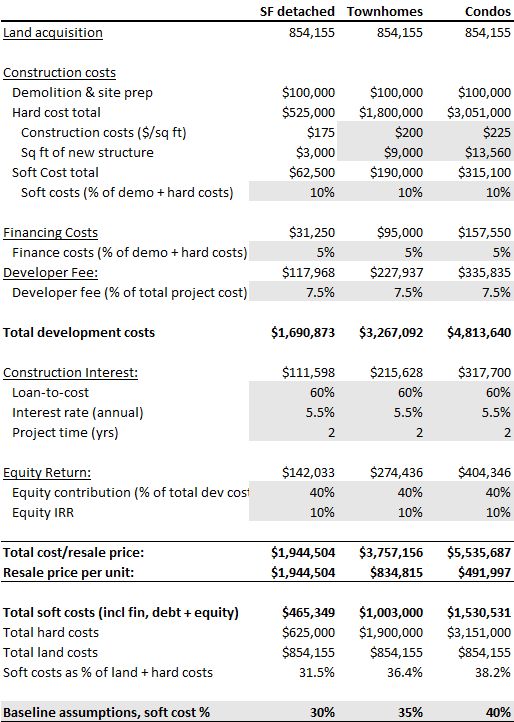

We develop estimated redevelopment costs for three structure types: a newly built single-family detached house, townhouses, and low-rise condos. The number of townhouses and condos per parcel is determined by the typical single-family lot size near each station area, as described in the previous section. Table 3 shows the land, hard costs, soft costs and total development costs for each structure type near the Wellesley Hills station.

The critical number in the financial analysis is the per-unit total development cost, shown at the bottom of Table 3. If a developer could reasonably expect to sell homes for that price (or greater), then she will be willing to undertake redevelopment. For the Wellesley Hills example, a developer would need to expect a market price around $830,000 for a townhouse and $500,000 for a condo in a small multifamily building. These development costs are well within the range of sales prices for recently sold homes in Wellesley, suggesting that redeveloping homes on single-family lots into higher density housing would indeed be financially feasible and attractive. Tables showing the detailed financial analysis for the other three station areas are available upon request from authors.

Our cost estimates include two components that represent the developer’s profit. One is a 7.5 percent developer fee, typically used to cover salaries for employees of the development company during construction. We also estimate a 10 percent return on equity investment, which represents the residual profits once the project is completed and the units are sold. Small-scale projects like these are typically undertaken by small, locally-owned companies rather than the large development firms that dominate big multifamily construction projects. This housing market segment tends to be fairly competitive, meaning that any individual developer has limited ability to set housing prices or extract excess profits. Therefore, developers will set the price of completed homes equal to the per unit cost of building them; for simplicity, in the remainder of the report, “cost” also indicates the price paid by homebuyers.

At all four station areas, townhouses and condos offer substantial savings for residents over new single-family detached homes (Figure 4). For all four station areas, the cost of a newly built single-family home is more than $1 million, while the cost of a condo is around $500,000. The reason for this discount is because land costs are divided among more homes. In the Wellesley example, acquiring a typical single-family lot would cost over $850,000.6 If the developer rebuilds a new single-family home, those land costs will be passed along to one purchaser. But under the townhouse and condo scenarios, the land costs are divided among five or 11 homebuyers, respectively. While the hard and soft costs of developing townhouses and condos are higher than single-family construction costs, land acquisition is a very large share of overall development costs. Increasing the number of homes per parcel yields substantially lower per-unit costs. The discount is largest for lots near Wellesley Hills and Beverly Farms, because land represents larger shares of development costs in those locations.

Legalizing apartments improves housing affordability around selected transit stations.

The Greater Boston region has been grappling with rapidly increasing housing prices in a tight housing market. To assess how upzoning around transit stations would impact housing affordability, we apply three lenses. First, we compare the price of redeveloped housing to existing home prices in each jurisdiction. Second, we compare the income needed to purchase redeveloped housing to the median income of each locality’s current residents. Third, we examine whether the estimated monthly costs of redeveloped housing would be affordable to voucher holders, subject to HUD’s Fair Market Rents.

Newly built condos would create relatively more affordable housing choices in Wellesley and Needham; new townhouses would also improve affordability in Wellesley (see Figure 5). The median home value in Wellesley as of 2018 was slightly over $1 million, or about $200,000 more than a new townhome. Only one quarter of existing homes in Wellesley are valued below $814,000, so new condos selling for around $500,000 would be a rare bargain. Condos would also fall in the lower quartile of home values in Needham Heights, while new townhouses would be slightly above the median home value ($805,000). In short, building condos and townhouses in these highly affluent and exclusive communities would make them more accessible to households who currently cannot afford to live there.

Redevelopment offers less clear affordability improvements in Beverly and Melrose, because their existing home values are substantially lower than in Wellesley and Needham. New condos would be priced close to the median existing home value in both communities, while new townhouses would be in the upper quartile. Redeveloping higher density housing would not substantially alter the affordability of the communities, although adding more housing would still create opportunities for additional households to live there, and ease pressures on demand elsewhere.

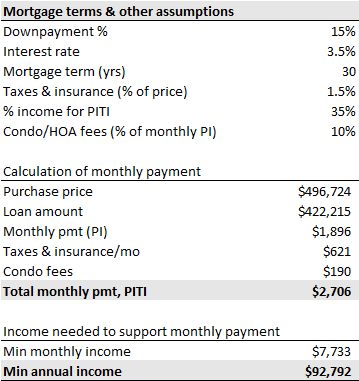

Our income comparison yields similar results. Starting with the purchase price of each new housing unit, we calculate the minimum annual income necessary to purchase that home. (Details on the mortgage terms and other assumptions used in the calculation can be found in Appendix Table 9.) Figure 6 shows that both townhouses and condos in Wellesley would be affordable to households earning $140,000 and $100,000, respectively, well below the $180,000 median income among existing residents. In Needham, households earning about $100,000 could purchase condos, while median income of existing residents is around $150,000.

Conversely, the income needed to purchase new townhouses in Beverly and Melrose (about $120,000) is actually higher than current median incomes in the communities. This illustrates how replacing older single-family homes with newer, moderate-density housing can gradually lead to rising incomes in some communities—a dynamic that low-income, Black and Latino communities throughout Greater Boston have already been experiencing because affluent suburbs block new construction. However, if older single-family homes are torn down to be replaced with new (usually larger) single-family detached homes, as is currently happening in many high-income communities, the new buyers would require even higher incomes than potential buyers of townhouses.

A potential benefit of legalizing moderate density housing is that townhouses and multifamily buildings are more likely than single-family detached houses to be rental housing. That opens the possibility that new apartments could create more opportunities for households who receive federal housing subsidies to access these communities. Our final test of affordability asks whether newly built housing could be accessible to low-income households who receive federal housing subsidies. Housing vouchers allow households to rent homes from private landlords up to a pre-set maximum rent, with the federal government paying monthly costs that exceed 30 percent of the household’s income. The Boston-Cambridge metropolitan area uses HUD’s Small-Area Fair Market Rents (SAFMR), meaning that the maximum allowable rent is determined at the ZIP Code level, rather than for the entire metro area. However, in many communities, it is nearly impossible to use vouchers because there is so little rental housing. The monthly cost associated with newly built condos in Wellesley Hills and Needham Heights is around $2,700—well below the SAFMRs for a two-bedroom apartment in these communities ($3,470 in Wellesley Hills and $2,960 in Needham Heights). The monthly costs of new housing in Beverly and Melrose are higher than the SAFMRs for those communities.

While it is difficult to estimate the broader regional economic impacts of legalizing duplexes, townhouses and apartments around rail stations, research shows that metropolitan areas with more flexible regulation of housing construction have seen slower growth in housing prices over time. Therefore, it is reasonable to assume that a statewide policy change that allows more moderately-priced housing to be built would, over time, contribute to less upward pressure on housing prices.

Neighborhood-level housing production

Two benefits of a statewide upzoning would be more homes within walking distance of rail stations, and an increased housing supply across the Greater Boston region. How much additional housing would likely be built within the next five years or so? We can extend the financial analysis—which estimates the number of units that could fit on a single redeveloped lot—to the neighborhood level, by simulating how many additional homes could be built within the half-mile distance of each of our four sample stations.

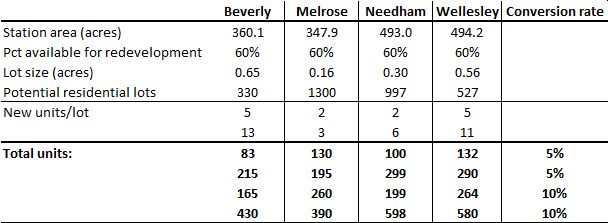

Our simulation assumes that 60 percent of the land area within one-half mile of the station would be available for redevelopment, acknowledging that some of the land will be needed for roads, sidewalks, retail and other non-residential uses (see Figure 7). The typical single-family lot size varies across our four stations, implying different number of existing lots available for potential redevelopment. We run the simulation using two different estimates for the share of existing lots that are likely to be redeveloped over a five-year period: a lower bound of 5 percent and a more optimistic estimate of 10 percent. These numbers reflect a gradual turnover of properties, typical of established neighborhoods. Our simulation focuses on a relatively near term of five years, because predicting construction costs and real estate prices for a longer time horizon introduces greater uncertainty.

As expected, redeveloping lots into small condo buildings would produce more new units than redeveloping them as townhouses. With the exception of Melrose, where the small typical lot size would accommodate only a three-unit building, the simulations of condo redevelopment generate more than twice as many housing units as townhouses. The neighborhoods around Needham Heights and Wellesley Hills stations offer the greatest potential for additional housing. Needham Heights has nearly 1,000 lots within one half-mile of the station, so redeveloping even 5 percent of those lots as condos could generate about 300 new homes. The typical lot near Wellesley Hills is very large, accommodating about 11 condos per lot, or nearly 300 homes in the neighborhood at a 5 percent conversion rate. While the lower conversion rate seems more reasonable over a five-year time horizon, simulations using a 10 percent conversion rate demonstrate even larger potential for more housing.

To provide some context for how large an increase in housing supply these estimates represent, we can compare them with how much housing each of these communities has built over the past five years. From 2015 to 2019, Beverly and Melrose issued permits for fewer than 200 new housing units in the entire jurisdiction—less than simulated condo production for just the half-mile station neighborhood. Wellesley permitted roughly 300 new homes in the entire town, and Needham permitted nearly 600 units. With the exception of Melrose, newly all new housing was in single-family structures (the most expensive type). Wellesley permitted one duplex building, otherwise entirely single-family.

Our production estimates are very conservative, because we model only one type of multifamily development. The policy proposal would also allow by-right apartment construction up to 20 units per acre on larger land parcels and converting non-residential buildings, which could generate substantially more units per project. Because of the idiosyncratic nature of large development projects, attempting to estimate the number of units generated by those projects is quite complex. Large projects are likely to require land assembly and more site preparation, both of which extend the completion time, so these projects are more relevant for longer-term projections.

To think about how a statewide zoning change might affect stations in different parts of the Greater Boston region, it is helpful to consider some groupings by distance and initial density.

Most stations in distant exurbs (beyond 15 miles from Boston) have lower land values, and thus would be less attractive for redevelopment in the near future. Stations inside the urban core (0-5 miles) also have some amount of single-family housing that could be converted to multifamily, if the state policy included a flexible or two-tiered density cap. For example, about 20 percent of housing within one-half mile of Porter Square station in Cambridge is single-family. The typical lot is quite small, around 4,500 square feet. Replacing these homes with four-unit multifamily buildings implies a density of roughly 40 housing units per acre, or twice the density we are modeling in suburban neighborhoods.

This illustrates the choices facing policymakers in writing a statewide zoning change: whether to regulate maximum density by building height, units per acre or some other measure has important implications for where multifamily buildings would be feasible. Establishing a two-tiered policy, allowing higher density within the urban core, would increase the policy’s effectiveness and reflect existing housing patterns. It is important to remember that zoning can constrain the size, density and type of housing that gets built, but increasing the density allowed under zoning by no means compels new housing to be denser. Because land values vary considerably within and across communities, the market will continue to build a variety of new housing types, resulting in a mixture of more and less dense neighborhoods.

4 Data sources and detailed description of variables can be found in Appendix Table 1.

5 These targets were chosen based on typical densities for new construction. The Census Bureau reports characteristics of new single-family and multifamily structures.

6 Economic theory suggests that upzoning land will cause land values to rise, reflecting the additional revenues that could be generated by building more homes. We conduct a scenario analysis that assumes land values rise by 15% for townhouses and 30% for condos. The discounts between single-family homes and denser structures is smaller under this scenario, but still quite substantial. Results shown in Appendix Table 7.

Over the past two years, policymakers in several states and localities have enacted or proposed initiatives aimed at reducing regulatory barriers to housing. The proposals described below provide some examples of how these policies can be designed, and the political challenges to enacting them. Notably, all successful zoning reforms have followed several years of campaigns dedicated to raising awareness of the issue and assembling diverse political coalitions in support. In most cases, the policy designs evolve over time to better address the needs of specific stakeholders.

California Senate Bill 50

One of the most ambitious zoning reform proposals to date is in California, where State Senator Scott Weiner has introduced two successive bills (Senate Bill 50, or SB 50, in December 2018 and Senate Bill 827 in January 2018). Senator Weiner introduced the initial SB 50 bill in late 2018, which sought to boost housing development near transit and jobs. Via SB 50, localities would be required to allow multifamily buildings up to five stories in any place located within walking distance of a rail station or high-frequency bus stop, or within a “job-rich” neighborhood. The bill would have also applied fourplex development by-right residential zoning statewide.

The SB 50 legislation attempted to change the practice of single-family-exclusive zoning, which prohibits building anything except single-family homes (plus an accessory dwelling unit) in nearly 80 percent of California’s residential neighborhoods. The measure received support from California YIMBY, a pro-housing lobbying group largely funded by Bay-Area tech industry executives, as well as from the California Association of Realtors, and a handful of environmental and housing advocacy organizations. However, the proposal was strongly opposed by local governments, anti-gentrification activists and suburban homeowners who objected to ceding land use authority to the state and raised questions about the impacts on housing affordability.

SB 50 did not pass, but did make it farther through the legislative process than its predecessor, SB 827, which was killed in committee. SB 50 underwent numerous revisions in committee, as Senator Weiner incorporated changes to win additional votes. The bill finally lost in a floor vote on January 31, 2020. Nonetheless, other changes made by the legislature have moved the state forward in ending single-family-exclusive zoning, including allowing homeowners to build two ADUs per lot in single-family zones.

Minneapolis 2040

With the City Council’s passage of a new Comprehensive Plan, called Minneapolis 2040, Minneapolis became the first major U.S. city to eliminate single-family-exclusive zoning in December 2018. At the time of its passage, more than 75 percent of city residents lived in neighborhoods that only permitted single-family or small multifamily housing. The comprehensive plan includes two major land use measures that seek to spur denser housing in more neighborhoods. First, the plan allows new three-to-six story multifamily buildings along high-frequency bus routes and near metro stations. Second, the plan legalizes triplexes by right in all parts of the city.

Minneapolis 2040 traces its origins back to City Council President Lisa Bender, who began heading the effort behind a comprehensive plan update in 2013. Bender and a progressive city council looked to implement more housing density across the city and received strong backing from Neighbors for More Neighbors, a Yes In My Backyard (“YIMBY”) advocacy group. Opposition to the plan’s zoning measures came largely from wealthy homeowners concerned about upzoning changing the character of their neighborhoods. To address said concern, city planners scaled back on the original plan to legalize fourplexes citywide, instead allowing for triplexes.

Although Minneapolis 2040 is a modest step toward enabling more housing production, the incremental density increases will produce different types of housing across different neighborhoods. Upzoning near transit corridors will encourage development of larger multifamily buildings with apartments designed for small families, while allowing duplexes into low-density areas will not noticeably change city streetscapes.

Oregon House Bill 2001

Oregon’s House Bill 2001 is the first successful statewide law ending single-family-exclusive zoning. Approved by the state legislature in June 2019, the legislation legalized the construction of duplexes statewide in cities with populations of greater than 10,000; and the construction of triplexes, fourplexes, attached townhomes, and some “cottage clusters” in cities with populations of more than 25,000. This means that only a few localities will still be able to have single-family-exclusive zoning restrictions.

Oregon cities retain the authority to regulate building size and design, intended to allow gradual change. Cities were also granted substantial flexibility to incentivize projects that create homes affordable to low-income residents. Introduced in January 2019, the bill received early and crucial support from Habitat for Humanity and other nonprofit affordable housing developers, coordinated by the Oregon Housing Alliance who saw the bill as helping more mid- and low-income households achieve homeownership. The bill also drew opposition from homeowners in the expensive Eastmoreland community (one of the first areas in the Portland metro to ban attached housing), the Eugene City Council and the Oregon League of Cities.

House Speaker Tina Kotek was instrumental in building bipartisan support for HB 2001, emphasizing the law’s capacity to increase housing diversity in many neighborhoods.

Virginia House Bill 152

In January, Virginia weighed a proposed statewide legalization of duplexes on all lots zoned for residential use. Introduced by Delegate Ibraheem Samirah in late 2019, the legislation sought to permit smaller, lower-cost homes throughout the state, especially in more expensive, urban areas reserved exclusively for single-family homes. Furthermore, the bill would allow localities to regulate the siting, design and environmental standards of “middle housing.”

H.B. 152 faced pushback in the House of Delegates, failing to move past the House's Land Use Subcommittee, and was tabled in early February. The bill received backing from Greater Greater Washington, an advocacy group favoring development around transit and jobs, as well as George Mason University’s Mercatus Center. However, the Home Builders Association of Virginia testified against the legislation, as did several local officials from across the state. Opposition to the bill was bipartisan, driven largely by committee members’ concerns about allowing the state to preempt local control on land-use.

Connecticut’s LCO 3508

Under a proposed bill currently under discussion in the Connecticut legislature, town officials would need to set aside land near train stations and commercial centers for developers interested in building moderately dense housing or other more reasonably priced housing. Sponsored by State Senator Saud Anwar, LCO 3508 proposes the statewide allowance of middle housing (buildings of at least four units) in at least 50 percent of the area within a ½-mile radius of a transit station, and 50 percent of the area within a ¼ mile radius of concentrated development. Town officials would need to set aside land near train stations and their town center for developers interested in building townhouses, duplexes or other more reasonably priced homes (not single-family residences). This bill is currently receiving support from Desegregate CT, a coalition formed to address housing disparities in the state.

Other Statewide Zoning Preemptions

Beyond efforts to increase density, other states have passed statewide zoning preemptions to encourage development.

Nebraska’s Legislative Bills 794 and 866

Nebraska State Senator Matt Hansen (D-Lincoln) introduced the Missing Middle Housing Act (Legislative Bill LB794) in January, which would amend local zoning codes to permit varied types of housing across the state. Similar to Oregon’s HB2001, the legislation would have mandated that all Nebraska cities with more than 5,000 residents allow “missing middle housing” in residential areas previously zoned exclusively for single-family detached residences. Middle housing is defined as low-rise multifamily housing such as duplexes, triplexes, fourplexes, cottage clusters and townhomes. The bill was postponed indefinitely in early August, although some of its provisions were included in Senator Justin Wayne’s LB866.

Sen. Wayne’s Density Bonus and Inclusionary Housing Act mandates that cities provide a regular report to the Legislature’s Urban Affairs Committee on the inclusion of middle housing and regulatory allowances or financial incentives for affordable housing. Furthermore, LB866 requires cities with a population greater than 50,000 to adopt an affordable housing action plan by 2023. Cities with a population of 20,000 to 50,000 would have to create such a plan by 2024. Cities that do not adopt an affordable housing action plan must adhere to a default plan that would effectively allow missing middle housing in all currently single-family zoned areas. LB866 passed through the Legislature on August 13 and was approved by Gov. Pete Ricketts on August 15.

Texas’ House Bill 3167

Amid concerns around the slow and nontransparent process for plat and land development application approval by political subdivisions, State Representative Tom Oliverson proposed House Bill 3167 to force cities to speed up the site plan/subdivision approval process. The bill, which became effective on Sept 1, 2019, required most Texas cities to make changes to their subdivision ordinance and/or zoning ordinance to enforce a response to a subdivision plat application within 30 days. Also known as the “shot clock bill,” the legislation also mandates that staff must respond to subsequent submittals within 15 days. If the city or county fails to do so, the plat or plan will be approved. To prevent reviewers from providing illogical comments to stall a development, the law further requires municipal authorities to provide a written statement of conditions or reasons for disapproval.

TECHNICAL APPENDIX

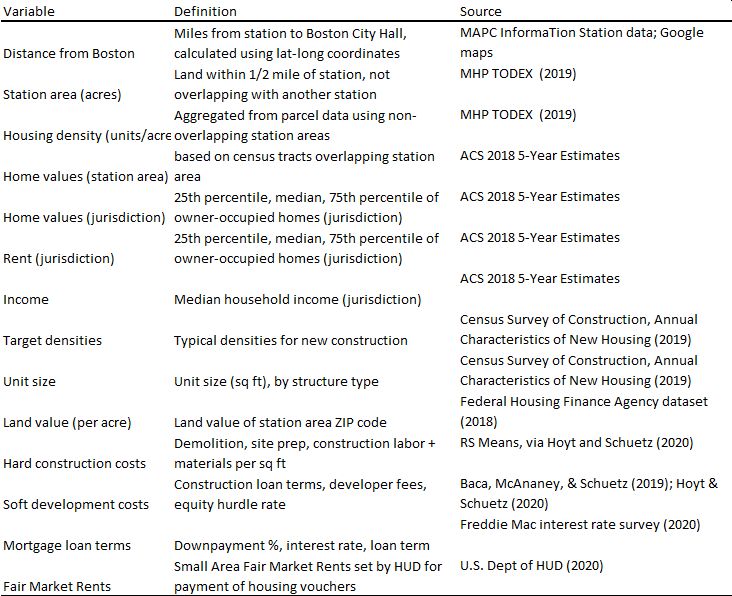

Appendix Table 1: Variable definitions and sources

Note: To merge the station area-level MHP data with the tract-level ACS data, we construct a ½-mile buffer around MHP’s plot of each rail station to build a station area. We then generate station area estimates for the various ACS indicators by calculating the percentage of the ½-mile station area within each census tract. This percentage is used to construct weighted averages for home values.

Appendix Table 2: Station area summary statistics, all commuter rail stations

Appendix Table 3: Typology of stations by location, density, and housing value

Appendix Table 4: Land acquisition costs

Appendix Table 5: Hard construction costs

Note: All cost category estimates are taken from pre-COVID-19 sources, because these are the most recent ones available.

Appendix Table 6: Detailed soft costs worksheet, Wellesley Hills

Appendix Table 7: Scenario Analysis

In addition to the baseline scenario presented, we assess the costs under four alternate scenarios. Each scenario tests whether less favorable conditions would reduce the substantial pre-unit savings from higher density development.

- Scenario 1: Hard construction costs increase by 10 percent for townhouses and 20 percent for condos, while single-family hard costs remain unchanged.

- Scenario 2: Soft costs for townhouses increase to 40 percent of hard costs and condos to 50 percent, while single-family soft costs remain at 30 percent.

- Scenario 3: Land acquisition costs increase by 15 percent for townhouses and by 30 percent for condos.

- Scenario 4: Land prices decrease by 10 percent for all structure types as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic and recession.

Appendix Table 8: Assumptions for station-area housing redevelopment

Appendix Table 9: Minimum income worksheet: Wellesley Hills

Starting with the purchase price of each newly built housing unit, we estimated the minimum annual income necessary to purchase that home. Appendix Table 7 shows the sample calculation for purchasing a condo in Wellesley Hills. Assuming standard mortgage terms for a 30-year, fixed-rate, fully amortizing mortgage, the monthly cost for principal and interest would be nearly $1,900. Adding in monthly escrow for property taxes, homeowners’ insurance and condo fees brings the total monthly payment to about $2,700. Assuming that households can spend 35 percent of their monthly income on housing costs, this suggests that the minimum annual household income needed to purchase the condo is nearly $93,000.