Upzone Update: Special Permits as a Counterintuitive Route for Permitting Reform

By Amy Dain

May 29, 2025

Upzone Update is back. Throughout 2024 we tracked and analyzed MBTA Communities implementation efforts. Now, with most local plans in place, we’re relaunching Upzone Update as a monthly newsletter to analyze the wider mix of zoning, building regulations, and related policies that shape housing supply across Massachusetts. We’re also welcoming housing policy expert Amy Dain as a Senior Fellow at Boston Indicators. She’ll author the newsletter and contribute to a range of other Boston Indicators research projects.

The MBTA Communities effort still matters, but it isn’t enough on its own to alleviate the region’s housing crisis. Upzone Update will analyze big reform ideas but also pragmatic, tactical fixes. And we’ll aim to clarify the policy trade-offs and the tensions between values that often get lost in the technical details. Our goal is simple: Keep you current on what’s being tried, what’s working, and where the state needs to push next to reach housing abundance and affordability.

The head-on solution to the housing shortage that restrictive municipal zoning generates would be for the state to undertake zoning directly—to designate and plan for (many) growth districts, and allow dense development in them, as-of-right. Until that becomes politically and managerially feasible, let’s consider an idea for another tiny step toward the goal of housing abundance, a compromise between state leadership and local control. Housing advocates may find the idea counterintuitive because it embraces special permits, which are commonly considered barriers to housing development.

The idea: The state could upzone existing walkable, amenity-rich, multimodal-mobile neighborhoods for up-to-six-story multifamily housing—by special permit, to be granted by municipal council or planning board. The state chooses the locations and creates opportunities; the municipality chooses the projects and maintains leverage over them.

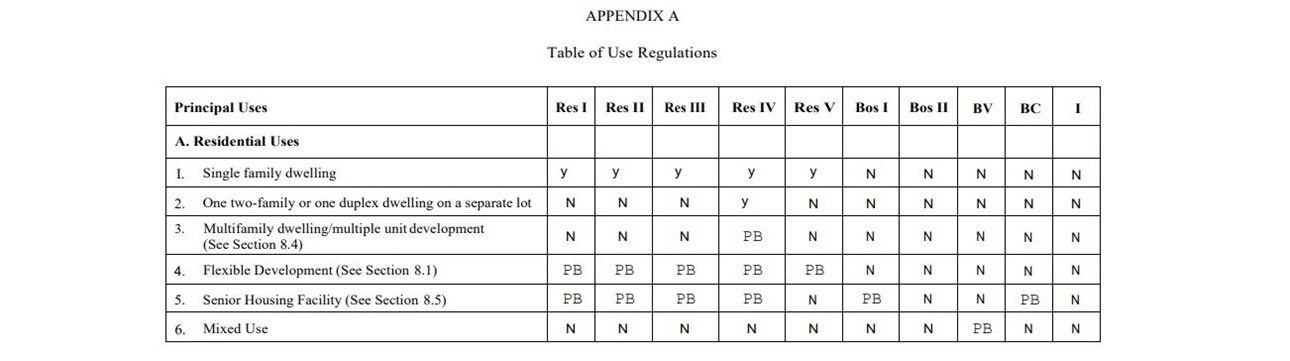

As it stands today, municipal governments decide, via zoning, where multifamily housing is A) allowed as of right (non-discretionary approval), B) allowed by special permit (discretionary permitting), or C) prohibited. Multifamily housing is outright prohibited (i.e., not allowed by right or by special permit) in most of the places that the market would favor. It is also often prohibited at the densities the market would favor. So, property owners frequently apply to municipal legislatures—city council or town meeting—to have their property rezoned to allow a given development. A significant (albeit uncounted) portion of multifamily developments statewide have had to win a rezoning to be eligible for permits.

Photo: (From 2018) Residences and retail in Lexington. Lexington Town Meeting deliberated on the proposal for this building at two annual meetings before approving the necessary zoning for it.

The state reform could include criteria for the SPGA to consider during project review. First, SPGA members could be instructed to consider the statewide need for housing production. Further, SPGAs might consider the adequacy of infrastructure like sewers and sidewalks; potential environmental impacts related to stormwater runoff, wetlands, and groundwater; access options for pedestrians, bikes, and vehicles; transportation systems; historic preservation; and other issues. SPGAs could require inclusion of first-floor retail as a condition of the special permit.

Housing advocates might shake their heads at this proposal. As a tool of local control, special permits have long been understood to undermine needed development. It is absolutely true that special permits add significant time, cost, and risk to the permitting process and construction, compared to as-of-right zoning. But not compared to the process of amending municipal zoning to allow a given multifamily project.

The state has set a goal of gaining 220,000 homes in the next 10 years. (Some experts think the need is much higher.) It makes sense to channel growth to neighborhoods where residents can walk to a train or bus, cafe, pharmacy, library, school, or park, for example, and have short commutes to work. Local zoning, as it stands now, will not see these goals realized, even after MBTA Communities re-zoning.

State-interventions to open the zoning gates generally can be grouped into a few paradigms:

- Nudges. For more than half a century, state leaders have called on municipalities to allow apartments. In the last 25 years, the state has spent millions helping municipalities create housing production plans and community development plans. Recommendations in plans have often remained vague, e.g., “Consider allowing multifamily housing by right on Main Street,” and unacted upon. Nudges have led to gradual, but way insufficient, progress.

- Carrots. The state has offered financial incentives for municipalities to upzone, for example with Chapter 40R, which has led to a tiny uptick in permitting. Under 40R, a city or town voluntarily adopts zoning districts where multifamily housing is allowed by right. Communities receive one-time incentive payments when a district is approved, and bonus payments once building permits are issued. So far, incentives have motivated small movements.

- Performance management. Under this approach, the state sets required standards for municipal zoning, but municipalities retain responsibility to enact the specific zoning rules. Despite rhetoric from opponents that MBTA Communities was “one size fits all” state control, the approach retained local control over the zoning. The MBTA Communities local rezoning process has taken several years, cost millions in planning assistance to municipalities, involved thousands of hearings and meetings, and resulted in a minor opening of zoning for homes. The result represents important incremental progress, but nobody is cheering to do it again. Municipal leaders have other business to attend to.

- State permission. Under this approach, the state either directly “zones” to allow certain uses and densities of development in certain locations, or exempts certain structures/uses from municipal zoning altogether. As an example, the state’s Affordable Homes Act (2024) exempted some accessory dwelling units (ADUs) from local zoning—in effect, directly allowing ADUs by right statewide.

The main drawback of the first three paradigms is that municipal rezoning for dense housing is incredibly hard to accomplish. The politics are typically brutal, the process slow, and the outcomes marginal or incremental. Massachusetts has 351 separate cities and towns. The juice-to-squeeze ratio is low.

Needless to say, the politics of the state bypassing local zoning, to bestow regulatory permissions for homebuilding, are also grueling. But, once done, the issue does not have to be revisited at hundreds of town meetings and city councils. And a state override of local zoning to allow housing by special permit should be easier to accomplish than an override for as-of-right permitting. This reform would support local planning, discretion, and control; it only shifts the democratic legislative decision-making to the State House.

This idea would not end the housing shortage. It would not make permitting of dense housing predictable and easy. It would lead to a small increase in the number of projects making it to construction. It would add to the recent incremental accomplishments of MBTA Communities, legalization of ADUs statewide, and the reform of the zoning vote threshold from supermajority to majority (for certain zoning changes). Little by little...

***

California Case Study: To learn about efforts in California to pass a state law to directly upzone areas near transit for multifamily housing as-of-right, check out this blog post by Jeremy Levine: “If passed, SB 79 would automatically change zoning rules to allow denser housing near train stations and high frequency bus lines, 6-7 stories within a quarter mile of transit and 4-5 stories within a half mile. Essentially, it sweeps away local barriers to housing in the areas its supporters believe make the most sense to build.”

MBTA Communities Update: The MBTA Communities law applies to 177 cities and towns. So far, 133 municipalities have adopted zoning to comply with the law (or already had compliant zoning). Four municipalities are now considered non-compliant, having missed a deadline to comply. The remaining municipalities have not yet reached their deadlines for compliance; votes are still to come.

There are numerous ways to assess the outcomes of MBTA Communities over time, but a key metric will be the basic count of homes permitted and built under MBTA Communities zoning. The Executive Office of Housing and Livable Communities (EOHLC) is keeping track of projects in the pipeline. EOHLC is using some judgment about which projects to include, so, for example, not counting projects that were only allowed by special permit within the district.

According to EOHLC, so far 18 municipalities have projects in the pipeline (or already built) under MBTA Communities zoning. More than 4,000 units are in the pipeline.

Lexington has by far the most, with a total of 1,097 units, in 10 projects. Note that this spring, Lexington voted to downzone its MBTA Communities zoning, reducing the district size and the allowed densities. Lexington was one of the first municipalities to adopt MBTA Communities zoning back in 2023, so there has been more time for projects to come forward than in Ipswich, for example, that just voted to approve new zoning this spring, 2025. But also, the originally approved districts in Lexington went beyond the minimum required by state law and covered many properties that were strong contenders for redevelopment (like large underutilized commercial properties).

Other communities with significant numbers of units in the pipeline include Westford (830 units), Everett (680 units), Amesbury (375 units), Taunton (275 units), Lowell (252 units), and Grafton (233 units). Many of these units are coming through large projects, as opposed to numerous small projects.

Somerville may be the community with the most projects coming through under the zoning, having permitted 23 triplex (three-unit) buildings.

Other municipalities on the list include: Arlington, Bedford, Danvers, Framingham, Melrose, Newbury, Newton, Norfolk, Quincy, and Revere.

Check out future editions of Upzone Update for more details about individual projects, and for updated numbers.

ARTICLES AND REPORTS

A study finds that Chapter 40B is good for social mobility: “Focusing on Massachusetts Chapter 40B, we find clear evidence that such policies build affordable housing in neighborhoods with strikingly greater opportunities for social mobility than are otherwise available to low- and moderate-income households. [...] An examination of underlying policy mechanisms suggests that 40B’s ability to bypass exclusionary zoning plays a central role in explaining differences in neighborhood characteristics between 40B and other programs.”

HUD reported in December that the number of people experiencing homelessness on a single night was the highest ever recorded. Boston Indicators released research in January on homelessness in Greater Boston.

Shira Schoenberg interviewed Yoni Appelbaum, in the Boston Globe. He compared Japan’s approach to land use regulation with US zoning: “In Japan, the central government continues to exercise a much stronger role. It’s created a dozen labels, and communities can apply those labels to different tracts of land. They can’t invent their own. They can’t layer on Byzantine rules. Every community in Japan plays with the same tool kit and applies it as it wants. That’s a much fairer process. It’s also one that allows builders to operate in different jurisdictions because the rules are familiar to everyone.”

It is worth taking another look at the report of the Unlocking Housing Production Commission, released in February. It makes recommendations for zoning reform, as well as many other reforms. On zoning: “The Commonwealth should eliminate parking minimums statewide for any residential use.” And: “The Commonwealth should allow two-family homes on all residential lots and four-family homes on all residential lots where there is existing water and sewer infrastructure.” (Note these recommendations fall in the category of “state permission,” direct exemption of certain things from zoning. These recommendations are not nudges, carrots, or performance management, per the above categories.)

Andrew Mikula and Salim Furth offer many ideas to streamline permitting of housing, in this Pioneer Institute report. For example, “Allow school impact fees in growing municipalities.”

Congressman Jake Auchnincloss talked about housing on the Ezra Klein Show: “Massachusetts has two bases that have been demilitarized, Fort Devens and Union Point—a tremendous amount of land there that is interstitial to local zoning regulations. Why don’t we have the big idea of the governor in the statehouse, either in Massachusetts or in California or another blue state, starting a new city and saying: We’re actually going to build 200,000 units of housing here. We’re going to ban cars and develop it so it’s more organic and walkable. That’s a big idea that I think could arrest some of the demographic backsliding we’re seeing in these blue states that are losing population and can’t provide housing affordability to their populations.”